The Elusive Geoduck : Reviled and Reveled

This large saltwater clam derives its common name, geoduck, from a Nisqually word which is said to loosely translate as “dig deep.” Don’t let their awkward looks deter you. Prepared right, this misunderstood bivalve is versatile and utterly delicious.

This large saltwater clam derives its common name, geoduck, from a Nisqually word which is said to loosely translate as “dig deep.” Don’t let their awkward looks deter you. Prepared right, this misunderstood bivalve is versatile and utterly delicious.

The geoduck is native to intertidal and sub-tidal waters from Alaska to California. With a shell that ranges from just 6 – 8 inches, the long siphon, or neck, makes it the largest burrowing clam in the world. In fact, a geoduck’s neck can be as long as three and a half feet in length. So large that even from when it is small as an inch, it cannot be withdrawn into the shell.

Geoduck attain maximum size at age fifteen, but are one of the longest living animals in the world. The typical lifespan of a wild geoduck can range to 140 years. The oldest being recorded at 168 years. Buried three feet deep in mud or sand, once they make it through their fragile adolescence, these giant clams do a fantastic job of keeping safe with their thick unpalatable skin.

Farmed geoduck

It takes about six years to raise a farmed geoduck to market. Beginning life in a hatchery tank, the small seed (about one inch long), are “planted” in the soft sand in the intertidal and protected with PVC tubes. The covered tube keeps them safe from predators until they are large enough to dig deeper.

Natural beds of geoducks grow on many of Washington’s public beaches with Puget Sound and Hood Canal containing the most abundant populations available for public digging. The best places to see experienced diggers capturing these big clams are at the Duckabush and Dosewallips State Park on Hood Canal. If you can’t harvest your own, head over to one of the restaurants and markets listed below or order fresh online.

Preparing Geoduck

Preparing a geoduck can seem overwhelming but it is surprisingly simple:

Boil a pot of water and prepare a bowl of ice water large enough to fit your geoduck. Using tongs, immerse the whole clam in the hot water for about six seconds.

Immerse it in the ice bath for about the same amount of time. Holding the shell with one hand, run the blade of your knife along the inside of the shell and extract the body from the shell.

Grasp the tough outer tube that surrounds the siphon meat and pull. The hot water and ice bath will have effectively separated the thick skin from the tender neck meat.

Discard the bulbous stomach and your efforts will be rewarded with tender meat from the body and the tougher but just as tasty meat from the siphon. The siphon meat is often ground to make chowder or patties.

Prepared Geoduck: tide to table

Just like being elusive to catch, geoduck can be difficult to find at restaurants. Fortunately in Washington some of the biggest producers of geoduck also have their own restaurants that they can supply this year round delicacy.

Here are a few South Puget Sound farmers that really know their Ducks:

Chelsea Farms and Oyster Bar

222 Capitol Way N

Olympia, WA 98501

Phone: (360) 915-7784

Chelsea Farms first made their mark on Olympia’s map in 1987 when Linda and John Lentz started their adventures in sustainable shellfish farming. Their legacy continues with the next generation, Shina and Kyle.

Taylor Shellfish Retail Store and Oyster Bars throughout WA

130 SE Lynch RD Shelton WA, 98584

PHONE: (360) 432-3300

Hours: Open for curbside pick up Monday - Sunday: 10am - 6:00pm; Closed all major holidays

Taylor Shellfish Farms harvests their own farmed geoduck from the Puget Sound. At their oyster bars across the state, diners can sample fresh geoduck sashimi with sesame ginger lime dressing. The giant clam is also used in Taylor Sheellfish Farms’ Northwest Chowder. Product also available online and shipped directly to your home.

Fjord Oyster Bank Restaurant

24341 N Hwy 101, Hoodsport

Phone: (360) 877-2102

Hours: THUR-FRI 5PM-8PM, SAT & SUN 1PM - 7PM | Closed MON-WED

The Fjord celebrates the recipes of Xinh Dwelley who was known for her acumen with geoduck. Available at the restaurant are sashimi, geoduck wontons, fritters, geoduck chowder, and ceviche. The Fjord sources their geoduck from commercial farmer on Harstine Island.

Step back in time this weekend in Matlock

The Old Timer's Fair celebrates Matlock’s timber heritage with living historic display and antique swap meet booths. Attendees enjoy kids’ activities, hand-crafted items, agricultural displays, food, prizes and live music.

This weekend, May 3-4, an army of dedicated volunteers from the tiny Mason County town of Matlock transform their local school grounds and invite attendees to step back to simpler time of homemade pies, tractor rides and country dances. This Rockwellesque celebration is the perfect way to get your family back into the swing of community events!

The Fair provides fun for the whole family and admission is free. Delicious country fair food – especially the homemade pies (try a piece and take home the whole pie) and a community welcome are the hallmarks of this decades old tradition. Enjoy living forestry and farming historical displays, craft and historical exhibits and find your feet tapping to the live music on two stages. One stage is indoor, with comfortable seating warm and out of the rain should a May shower visit the event.

The fair celebrates Matlock’s heritage in the timber industry, with draft horses, early day machines and motors as well as blacksmithing and an entire gym filled with antique booths. In addition enjoy kids’ activities, hand-crafted items, historical events, agricultural events, food, a firewood raffle, prizes and live music.

Most of the displays are inside and surrounding the school buildings and be sure to stop by the John Tornow exhibit located anear the main stage.. This is the story an "Unsolved mystery," a century later. “Victim or Villain?” is the true story of events a century old. John Tornow lived in the Matlock area and his memory lives on her e and at the Matlock Historical Museum open during the Fair.

Other attractions include kids train rides, tractor pulls, plant and starter vegetable sale, crafts and antique booths, and live demonstrations of the Dolbeer steam donkey. Sunday features antique and classic cars , tractors and steam engines. Saturday enjoy a pulled pork dinner and silent auctions. There will also be a corn hole championship new this year!

This year the event is hosted May 3-4 with the fair open 10:00 AM – 6:00 PM on Saturday and 10:00 AM – 4:00 PM on Sunday.

The event is located at 2987 Matlock-Brady Rd., about five miles south of the Matlock store and 15 miles north on Highway 8. For additional details visit the event page. FREE

Pedaling the historic tracks

Here’s what to expect when you pedal the rails on the historic Simpson Logging tracks near Shelton.

Vance Creek Railriders, located near Matlock, is a popular activity near Shelton, WA. Have you made your reservations yet?

The rails are part of an old track built by the Simpson Logging Company, so along with clacking past beautiful wooded scenery, passing meadows of foxgloves and crossing over creeks lined with ferns, Vance Creek’s rail journey follows a snapshot of the Northwest’s rich logging history. Until not that long ago, timber trains moved logs along these very rails to the mills in nearby Shelton, in fact this system was the last operating privately-owned logging railroad in the continental US.

When you arrive, don't be alarmed when you leave the main road for a short hop on a gravel logging road to Camp 1. The gravel road is well maintained (even the school bus follows it in rural Mason County), you will soon find yourself at the Vance Creek Railriders office. Arrive 30 minutes early as there is a safety briefing before heading out to get adjusted in your seats.

What to Expect

As you pedal the multi-seat "railrider" along the track you will have the opportunity to see old growth and new forests as well as diverse meadows teeming with wild flowers, moss, and maybe even catch a glimpse of some wildlife – although cheering, laughter and distinctive trail clacking seems to put them on the alert! You will pedal down across the winding Goldsborough Creek and return back up the gradual grade.

Yes, despite its leisurely pace, this is a physical adventure. Most guests are able to pedal the average .75% grade back up to Camp 1 with a portion of the rail at a 2% grade (it’s all downhill on the way there) . But don’t worry – if you struggle, the little “engine” will give you a push back up the slight grade if needed.

This gentle, but vigorous ride is suitable for (and enjoyed by) all ages. Chidren under 12 years old need to be accompanied by an adult on their railrider (four seats). The typical age to be able to help pedal is 6-8 years old depending on leg length. Smaller children who can’t touch the pedals or who are known to be a wiggle worms can use a car seat. Visit the Vance Creek’s FAQ page for answers to common questions.

Be sure to dress in layers as you will be traveling in wooded area where it can go from shade to sun. Also bring snacks and water bottle as the location of the start of the railride is fairly distant from Shelton.

Reserve in Advance

Opening Day is May 17, 202

The popular pedal-powered rail rides with Vance Creek Railriders opens for their 2025 season on May 17 with daily departures of the 2-hour excursion at 9 AM, 12 PM, and 3 PM, Thursday through Monday. Arrive 30 minutes early to check in and hear a safety briefing.

The rail head is at 421 West Hanks Lake Road, nine miles west of Hwy 101 on the Shelton/Matlock Rd.

Rowboats and Recitals: The Story of Mason County’s Early Schools

In this feature, Explore Hood Canal visits the Mason County Historical Society Museum in downtown Shelton to explore “More Than a Building,” a powerful exhibit on the early schools of Mason County. Featuring insights from curator Liz Arbaugh, this video reveals how schools were the heart of tiny communities—from tribal lands to logging camps.

What if I told you the quiet forests and mossy clearings of Mason County once echoed with the sound of children learning—and even rowing boats just to get to class? In this feature, Explore Hood Canal visits the Mason County Historical Society Museum in downtown Shelton to explore “More Than a Building,” a powerful exhibit on the early schools of Mason County. Featuring insights from curator Liz Arbaugh, this video reveals how schools were the heart of tiny communities—from tribal lands to logging camps.

📍 Visit the museum: 427 W Railroad Ave, Shelton, WA 98584

👨💻 Online: www.masoncountyhistoricalsociety.org

🗂️ View the exhibit and the Dayton archives

🎄 Learn about schoolhouse dances, Christmas parties, and how education shaped this region

💬 Leave a comment if you remember your Mason County school days!

#MasonCountyHistory #SheltonWA #HistoricalSchools #PacificNorthwestHistory #ExploreHoodCanal

Roam Wolfdog Sanctuary Offers Education Tours

Nestled in the forest outside Shelton in Mason County, the ROAM Wolfdog Sanctuary provides a home for some of the most misunderstood animals in the world—wolfdogs.

Story: Jeff Slakey

Amongst the woods outside Shelton, off Highway 101, the ROAM Wolfdog Sanctuary provides a home for some of the most misunderstood animals in the world—wolfdogs. On a sprawling 40-acre property, the sanctuary educates the public, advocates for conservation, and provides a safe, enriching life.

photo credit: ROAM Wolfdog Sanctuary

Every wolfdog at ROAM has a story, and most share a similar beginning. They were bred to be pets, then abandoned or surrendered when their owners realized they weren't suited for a domestic lifestyle. "All of these animals here were bred to be somebody's pet," explains Jody Woolard, sanctuary's founder. "They want to mimic something that looks like it just walked out of Yellowstone Park, but they require a lifestyle that most people aren't prepared for."

Unlike dogs, wolfdogs have wild instincts that make them difficult to manage in a home environment. They require large enclosures, an all-raw diet, and specialized care. Many are high-content wolfdogs, meaning they have over 90% wolf DNA. While some enjoy meeting people, others take their time warming up to new faces.

One of the biggest misconceptions about wolfdogs is that they make good guard dogs. In reality, they tend to be skittish rather than protective. "They are not house pets," Woolard says. "They need to be outside. They need enclosures with eight-foot-tall fencing and dig guards so they can't escape."

Their diet is also unique. "They eat raw," says animal caretaker Reanna Warren. "Chicken, steak, pork—sometimes beef, but they're picky. They won't touch boneless, skinless chicken, and if it's ground beef, it has to be frozen."

ROAM is not only a shelter—it's a permanent home for its residents. Each enclosure spans about an acre, giving the animals space to roam while protecting the public. "We try to create an environment for them that is as natural as possible," Woolard says. "In the winter, we get snow, which they love. And in the summer, the forest keeps it from getting too hot."

Community plays a role in keeping the sanctuary running. Volunteers come to help clean enclosures and construct new habitats. Food donations come from local grocery stores and hunters. For visitors, a tour of ROAM is a chance to see these animals up close and learn about wolves' vital role in the ecosystem. "Wolves keep deer and elk populations in check, which benefits many other plant and animal species," explains Woolard. "But in some regions, they're still being hunted. Nearly 1,000 wolves in the Northern Rocky Mountains were killed last year alone."

Touring ROAM

Tours at ROAM last about 90 minutes and offer an up-close look at the lives of these animals. Visitors can witness a playful interaction between Issabel and Kovu, a bonding moment between Pretty Boy Floyd and Felony, or even hear the pack's haunting howls echoing through the trees. "Two of our neighbors leave their windows open at night just to hear the howling," Woolard shares.

As a nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization, ROAM relies on donations and sponsorships to continue its mission. "Every year, wolfdogs are abandoned, rescued, or euthanized because people purchased an animal they weren't prepared to care for," says Woolard. Sponsorships cover food costs, medical care, and facility maintenance, ensuring the wolfdogs can live out their life safely and comfortably.

Another way you can help is by spreading awareness about ROAM, the wolfdogs, and the importance of conservation. "Education is key," Woolard says. "The more people understand these animals, the better we can protect both them and their wild counterparts."

So, if you're a wildlife enthusiast, an advocate for conservation, or someone looking for a unique experience in Mason County, a visit to ROAM Wolfdog Sanctuary is sure to leave you with a newfound respect for these remarkable animals.

To learn more or schedule a tour, visit their website, roamwithus.org or come to ROAM with the pack. The Guided Educational Tours at Roam cater to wildlife enthusiasts, animal lovers, students, and families seeking an enriching and educational experience. This exclusive opportunity allows guests to engage with wolfdogs in a meaningful way and support the sanctuary's mission of promoting coexistence and understanding between humans and wildlife.

Lower South Fork Skokomish River trail

Take a hike, run, horseback ride or bike ride on an inviting trail along a wonderful stretch of the river. Admire surviving groves of towering old-growth, recovering old harvest areas, and a watershed coming back to life.

Craig Romano | Story & Pictures

One of the most heavily logged watersheds in the Olympics—clear cutting and increased sedimentation has taken its toll on this vital river. But in the last two decades a diverse consortium of agencies, non-profis, Skokomish Tribal members, business interests and local folks have begun the process of restoring the South Fork Skokomish back to being a healthy and productive river.

Take a hike, run, horseback ride or bike ride on an inviting trail along a wonderful stretch of the river. Admire surviving groves of towering old-growth, recovering old harvest areas, and a watershed coming back to life.

Hit the Trail

The South Fork Skokomish River along with the North Fork form the Skokomish River in a broad valley in the Olympic Mountains foothills. Here the river flows a short distance east to a large delta at Hood Canal’s Great Bend. It’s the largest river system emptying into Hood Canal. The North Fork is dammed at two locations, while the South Fork flows freely. However much of the South Fork faced major degradation due to extensive logging. Where it flows through national forest and private timberland once contained one of the densest concentrations of logging roads in the state.

Before logging began at a rapid pace after World War II, the Skokomish River, especially its North Fork supported healthy runs of Chinook salmon, steelhead and bull trout. The river is within the traditional lands of the Twana People which comprise of the Skokomish Tribe. Skokomish means “big river people.” The Skokomish People had four winter camps along the North Fork and several summer camps used for elk hunting along the South Fork. Since watershed restoration has begun fish runs have improved. Elk herds in the watershed remain healthy although numbers have recently decreased causing some concern among biologists and wildlife managers.

A trail once ran for more than 40 miles from the settlement of Mohrweis near the river’s South and North Forks’ confluence all the way to the South Fork’s headwaters near Sundown Pass in Olympic National Park. Logging on private and national forest land has obliterated more than half of the historic trail. What remains of the trail was truncated by a Forest Service Road creating a Lower and Upper South Fork Skokomish River Trail.

The upper trail is wilder leading into the national park and is often inaccessible for more than half of the year. Much of the lower trail is open year round making it a wonderful choice for a spring hike.

The lower trail is more than 10 miles long making it a great choice for a long run or bike ride or a one night backpacking trip. But to do the whole trail involves fording the river at 8.6 miles which is dangerous and difficult much of the year. By mid-Summer the river’s usually just shin deep and safe to ford.

From the main trail head on Forest Road 2353 the trail immediately starts climbing and steeply. After ascending about 350 feet up a high bluff above the roaring river, the trail enters a magnificent old-growth grove of Douglas-firs, some over five hundred years old.

As the trail nears the crest of the bluff, a half mile spur trail heads right through beautiful primeval forest to the LeBar Creek Horse Camp. Equestrians usually use this trail head as their starting point on this trail. Just beyond, another path leads right reaching a Forest Service Spur road in a quarter mile.

It offers an approach to avoid the initial climb. The trail now via short, steep switchbacks, drops back to the valley floor. Expect to get your boots wet crossing a cascading creek at the base of the bluff. Then traverse a beautiful glade of mossy maples and alders.

The trail now on a gentle grade passes by more old Douglas-fir giants, as well as a few stumps of cedar giants that were sent to the mills many years ago. At about 1.5 miles the trail reaches a low bluff with a great river view—a good destination for a short hike. From here it continues upriver crossing a side creek in a big-timbered ravine. After a stretch of boardwalk the trail reaches a junction with a trail leading to Forest Road Spur 140. Almost immediately afterward the trail reaches Homestead Camp about 2.2 miles from the main trail head. Here an old ranger guardhouse once stood.

Continue through luxurious river bottom lands crossing more creeks that may wet your boots. The way then pulls away from the river, before dropping back again toward the roaring waterway. The way then traverses more old growth and crosses more side creek, these thankfully are bridged. Admire a nice little cascade before climbing a small bluff. The trail then once again switchbacks down to river level coming to a couple of junctions.

The trail right leads to Forest Road Spur 2355-100. The short spur left leads to Camp Comfort along a wide gravel channel on a river bend. Here at about 5.0 miles from the main trail head is a good turn around spot for a day hike.

If you decide to go farther along the trail;, the way soon reaches an incredible overlook of the river on a bluff high above a big bend, where the river has eaten away at the bluff and trail in the past. Beyond the bluff, the trail is lightly traveled and a little brushy in spots.

It continues on an up-and-down course, before reaching the ford of the South Fork Skokomish (safe only in low flows) at 8.6 miles. It then comes to the historic Church Creek shelter. From here, the tread improves and the trail continues upriver, passing inviting Laney Camp and the spur to the old Camp Harps Shelter site.

At 10.3 miles from the Main Trailhead the trail reaches its upper trailhead on FR 2361 (accessible when FR 2361 is open from May 1 to Sept 30). Beyond, the trail continues as the Upper South Fork Skokomish River Trail traversing old-growth forest and a wilderness valley spared from logging.

Whale watching from the Shores in Hood Canal

The whales are in Hood Canal! These last few weeks Hood Canal and South Puget Sound have produced a lot of exciting sightings of whales in the area.

Walking along the shores of Hood Canal and the waters of Hammersley Inlet you can spot many interesting marine creatures from the lowly (yet delicious) Olympic oyster to the lumbering California sealion. Although not as dependable as catching a glimpse of a harbor seal, or a great blue heron, the sight of an orca (Orcinus orca) is perhaps the most rewarding.

With newborn calves weighing as much as 400 lbs, orcas are the largest species within the oceanic dolphin family. Full grown female orcas may reach lengths of 18-21 feet and weigh as much as 9,000 lbs and males can get to be 21-24 feet and weigh as much as 12,000 lbs. Because of their size these giants need to eat 150-250 pounds of food a day to survive.

Usually traveling in multi-generational pods of two or more family groups, lead by older matriarchs (grandmas) these whales are strongly devoted to family.

The matriarchs have been observed to aid in the raising of their grandchildren (in a way similar to human grandmothers) and, like human females, they live many years past their reproductive age.

The eldest sons and daughters of matriarchs tend to stay with the family unit (or matriline). Researchers using specially adapted microphones hung underwater, have documented that each matriline has distinctive calls special to it and apparently understood within the pod.

This has led some scientists to argue that orcas have dialects and languages, something that no other animals are documented as having (beyond humans).

Orcas are found across the globe, usually favoring cold waters, but they swim to tropical waters to moult their skins. In the Pacific Northwest, researchers have documented three populations of orcas which have distinct feeding and social behaviors: the Transients who prey on other marine mammals, such as dolphins and seals;

The Residents who find sustenance primarily in chinook salmon; and the little understood offshore orca that are found from California to Alaska and are purported to eat fish and varieties of sharks. According to researchers there are no obvious biological reasons why these whales eat such specific food.

In fact, this preference may be starving the chinook dependent Southern Resident whale population seen in the inland waters of the Salish Sea (Puget Sound, the San Juan Islands, and Georgia Strait), which are in such small numbers they are listed as endangered in both Canada and the United States.

Researchers have been struggling to save these whales and understand why they do not diversify their feeding habits. The most interesting argument researchers have made is that the Southern Residents, although physically able to eat sea mammals or other fish, have established taboos within their groups that prohibit them – in an essence they have cultural constraints, such as seen amongst humans refusing pork or beef on cultural grounds.

Additionally, Residents and Transients have been observed to actively avoid one another, which is reflected in the fact that the Transients tend to visit the waters of Southern Puget Sound between the months of March and September, when the Southern Residents make their migration out of the Southern Puget Sound area. Genetic research has further revealed that there is no interbreeding between these two groups– almost as if they were a different species.

The Southern Residents may be seen chasing the chinook on their upriver run during the fall from several easily accessibly points on shore: on Hammersley Inlet from Walker Park (near Shelton), on Totten Inlet from the Arcadia Point Boat Launch, on Case Inlet at Latimers Landing, and at the Allyn Waterfront Park.

Along the Hood Canal orcas are more rare, but this Spring, a pod of Transients was spotted several times from the Hood Canal Bridge all the way down to Belfair. This group stayed in the area for quite a while much to the delight of the shore residents.

Before you head out to look for whales, check out the many online resources provided by the Orca Network. They offer a constantly updated list of orca and whale sightings. In May the reports on the Orca Network Sightings orcanetwork.org logged orca sightings along Hood Canal from vantage points at Dabob Bay, Brinnon, Seabeck, Lilliwaup, Potlatch, Union, and Tahuya.

If you plan to search from the shoreline a good pair of binoculars and a zoom lens are recommended. Look for sudden sprays of water and the tell-tale black dorsal fin. If you are searching by boat, exercise caution and remember you are a guest in their waters.

If you see a blow go slow, it is the law in the US to travel less than 7 knots and stay at least ½ mile away when traveling by boat near orcas. If the orcas come closer than 300 yards to your boat, you must turn off the engine, as the noise from the engine can confuse the whales and there are many accidents resulting from props and whale collisions. Also fish finders and depth sounders should be turned off when not in use.

http://www.orcanetwork.org

A convocation of eagles

A convocation of eagles is not a feted occasion requiring black gowns and tasseled caps. Like a murder of crows or a gaggle of geese, a convocation is the unexpected collective noun for a group of eagles.

A convocation of eagles is not a feted occasion requiring black gowns and tasseled caps. Like a murder of crows or a gaggle of geese, a convocation is the unexpected collective noun for a group of eagles.

Eagles have inspired humans throughout history – and the world. The Ancient Romans used them as a symbol of Empire. Here in the United States, the Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) is our national bird.

Native American tribes, including Hood Canal’s Skokomish, venerate the Bald Eagle. Many tribes associate the eagle with the creator. Since this bird is the strongest flyer, it is believed to carry prayers to the heavens. Feathers and other parts of the bird (such as the talons) are important to many Native American ceremonies, such as smudging, powwows, and talking circles.

At the turn of the 18th century, the Bald Eagle population was estimated to be between 300,000–500,000. In the early 20th century however, the eagle was targeted for sport and because of their perceived predation upon livestock. Between 1918 and 1930 one ornithologist estimated that approximately 70,000 bald eagles had been shot in the state of Alaska. Additionally, nesting sites were disturbed by logging and other forms of development.

The Bald Eagle Protection Act was introduced in 1940 to protect nests, eggs, feathers, and to stop the slaughter of Bald Eagles. By the 1950s, however, there were reported to be only 412 nesting pairs left in the 48 conterminous United States.

Pushed to near extinction

Further, pressure was placed upon Bald Eagles populations (and many birds of prey species) by the pesticide Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT). Since Bald Eagles are predators at the top of the food-chain, this chemical was concentrated in their prey and even the prey of their prey. This bioaccumulation disrupted the Bald Eagle’s metabolism of calcium, severely effecting fertility rates and inhibiting healthy egg production.

Bald Eagles were declared endangered in 1962.

Shari Sommerfeld Images

Revival of a species

However, this is actually a happy story. In 2007, the Bald Eagle was federally delisted from the endangered species list. With the banning of DDT in the United States in 1972 (1989 in Canada), extensive breeding programs, and the enforcement of the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act– the population soared. By 2005, in Washington State alone, it was estimated that there were over 840 breeding pairs. In 2009, the Bald Eagle population of the United States was estimated to be nearly 143,000 birds, this number is expected to stabilize at 228,000 birds in the next 5 to 15 years.

Speaking of resurgent populations, January to February is the mating season for Bald Eagles. Usually mating for life, male and females perform stunning aerobatic courtship displays with airborne talon clasping and free falls.

Along the Hood Canal, nests are in trees near water or open fields. Old cedar snags, giant spruces, or the larger coniferous trees are favorites. Both the male and female gather branches and twigs to weave into these monstrous nurseries.

Eagle nests, known as aeries or eyries, are one of the largest nests at nearly 5-6 feet in diameter and 2-4 feet in height.

The female will typically lay 1-3 eggs and both the male and female will take turns incubating the eggs for 34-36 days. After 10-12 weeks (approximately late summer), when the fledglings have left the nest, the mating pair and fledglings may travel to Northern British Columbia and Alaska to take advantage of the early salmon runs.

Shari Sommerfeld Images

To learn more about birding locations on Hood Canal, visit olympicbirdtrail.org for a list of 25 top locations around the peninsula.

A Few Eagle Facts

Bald Eagles are not actually bald, their name comes from an older term for “white- headed.”

At 80.3 inches, the Bald Eagle’s wingspan is slightly greater than a Great Blue Heron. Mature Bald Eagles can weigh between 105.8 to 222.2 oz, with the females usually weighing in on the larger end of the spectrum.

The Bald Eagle is the only eagle native to North America. There are other eagle species in North America, but they are found more globally too, whereas the Bald Eagle is specifically found in North America.

Bald Eagles have a long-life span. The oldest recorded bird in the wild was killed by a car in 2005 in New York, 38 years after being banded in the same state in 1977.

Bald Eagles have a soft, chirpy call, which runs counter to the image of a strong, powerful bird, so its call is often dubbed over in TV and movies with the call of a Red-Tailed Hawk.

Bald Eagles are capable swimmers, if their free-fall salmon dive results in a catch that is just a little too large for lift-off, they can swim ashore with their catch, using their massive wings as “oars.”

Don’t keep an illegal eagle! Possession of an eagle feather without a federally approved permit may be punishable by a $100,000 fine and/ or a year in jail. Permits are only granted to federally recognized Native American Tribal members.

10 Myths & Facts about Great Blue Herons

It’s a common sight to see the “lucky” great blue heron patiently hunting on the shores of Hood Canal and South Puget Sound. Largest of the heron species, up to 4’ in height, they actually only weigh between 5-6 pounds. Here are a few things you may not have known about these iconic Northwest birds.

It’s a common sight to see the “lucky” great blue heron patiently hunting on the shores of Hood Canal and South Puget Sound. Largest of the heron species, up to 4’ in height, they actually only weigh between 5-6 pounds. Here are a few things you may not have known about these iconic Northwest birds.

MYTH

Great blue herons only eat fish.

Great blue herons dine mostly on fish but they will also stalk everything from insects to small mammals and even other birds. In Washington, mice and voles making up a major portion of their winter diet when they choose to hunt on land.

2. FACT

Herons spend about 90 percent of waking time stalking prey.

Great blue herons grab prey in their strong beaks or use their dagger-like bills to impale. This action is known simply as a ‘bill stab’. They shake the prey to break spines before gulping them down. Great blue herons can swallow fish that are much wider than their narrow neck and have even been know to catch small birds in flight. Patience and speed are the keys to their hunting success.

3. MYTH

Great Blue Herons are cranes.

A crane is totally different type of bird. You can tell them apart by looking at the beaks and the way they fly. Cranes have shorter beaks and hold their necks straight when in flight, whereas herons curve necks into an S-shape. Herons are able to do this because of specially shaped vertebra. Great blues also fly with their legs ‘hanging” which is unique from most birds.

4. FACT

Herons are often called “Dinosaur Birds.”

Fossil records date them back 1.8 million years ago, but they are thought to have existed about 25 million years ago during the Cenozoic age. Maybe it’s also because of the prehistoric sounds they make as they take off with the giant 6’ wingspan flapping!

5. MYTH

Great Blue Herons can’t swim.

The great blue does many things that other herons choose not to do, including swimming in deep water with apparent grace and comfort. A quick search on the internet will show multiple accredited images of herons happily swimming in deep water. It’s not a common occurrence though, so consider yourself lucky if you catch sight of this phenomena. Swimming is a testament to the great blue heron’s incredible adaptability.

6. FACT

Great blue herons have adapted “bib” feathers to keep them clean.

Specialized feathers on their chest grow continuously and fray into a fine cleaning powder. This powder is used to help groom their entire body and clean off fish slime.

7. MYTH

Great Blue Herons are monogamous.❤️

Not technically. Great blues are known to be ‘serial monogamous’ — they have one partner for a year but choose a different one each mating season. Despite being territorial with other herons, they typically breed in nesting colonies at the tops of trees containing up to 500 breeding pairs. These colonies are called “heronries.” They obviously do not have any social distancing issues. Great blue herons generally return to the same breeding grounds each year although with different partner choices.

8. FACT

Mates work to build the nest, as well as incubate and feed their young –together.

When the mating pair is chosen, the male gathers sticks while the female weaves them into a platform nest lined with moss, grass, and small branches. She lays 2-6 blue eggs, and both parents take turns incubating them for 4 weeks until the young hatch. They also take turns feeding regurgitated prey to the young chicks.

9. Myth

Heron chicks have yellow eyes when they are born.

Heron chicks have gray eyes when born that become bright yellow when they are adults. The parents continue feeding the nestlings for a few weeks after fledging (leaving) the nest. Young herons will fledge at around two months.

10. FACT

Great blue herons’ colors can demonstrate age, sex, and mating season.

Adult males are larger and generally have brighter orange legs than a female. During breeding season, the lore (the lore is the region between the eye and bill) will turn a bright blue, the iris will turn reddish, and the yellow bill will take on an orange hue.

A couple other things you didn’t need to know about great blue herons:

To keep cool they flutter their throat muscles to increase evaporation.

It can take up to two weeks to build a nest.

Life expectancy of a great blue heron is 15-23 years

Despite their size they can fly as fast as 30 MPH.

An adult heron consumes up to one pound of fish per day.

Learn more

The Cornell Lab - all about birds

Audubon - Great Blue Heron guide

Olympic Bird Trail - Top birding locations on Hood Canal, South Puget Sound, Pacific Coast, and Olympic Peninsula

Tips for taking your dog to The park

For dog families, it’s not a hike, camp out or road trip unless your four-legged trail buddy comes with you. While embarking on the adventure is optional, getting back healthy and whole is mandatory! Washington State Parks has some tips to leave you with only good memories when you visit.

For dog families, it’s not a hike, camp out or road trip unless your four-legged trail buddy comes with you. While embarking on the adventure is optional, getting back healthy and whole is mandatory! Washington State Parks has some tips to leave you with only good memories when you visit.

Trail tips

We know your dog wants to run free, but leash rules are not a punishment – they’re there for everyone’s safety. Your pup may be a big softie, but even saying, “It’s okay, they're friendly,” won’t assuage some peoples’ fear. Keep your dog from approaching people unless someone asks to pet him or her. Conversely, if your dog is not dog or people-friendly, please warn folks – especially children, before they get close.

Predator or prey?

In the natural pecking order, a dog can be seen as prey to some wildlife (raptors, big cats, coyotes, black bears) and a predator to others (deer, rabbits, marmot, turkey, horses). Leashing your pet can be the thing that keeps them from dinner – both eating and becoming.

Keep in mind that most prey will fight back, and getting gored by a deer is not how you want your pup to end their vacation. Also, when dogs chase wildlife – or something they see or smell – they can get lost or into deep water. Even if your dog is behaved at home, parks are abnormal environments that might be tempting for an off-leash dog to ignore. Tricky whales, seals and waterfowl have been known to lure dogs out into the water and exhaust them.

Trail hazard?

On mixed-use trails, heel or pick up your pooch if a horse or a mountain bike comes by. A horse can easily spook and injure itself, its rider or your party. Mountain bikes zip downhill at high speeds, and you don’t want your dog to chase and get in an accident.

Be my neighbor?

Camping with dogs is just fun. Pups provide warm cuddles and a feeling of safety for solo campers. And dogs + kids + snuggles in the tent go together like chocolate, graham crackers and marshmallows around the campfire.

But dogs hear and smell things we don’t, and they often feel the need to alert us. Your neighbors, however, may not appreciate Fido howling a warning at 2 a.m.

Consider booking a campsite on the end and/or outside part of the campground loop. One Parks staffer says she parks her car between her site and her neighbors’ to minimize stimuli.

Most parks welcome dogs, but we do have a few culturally or environmentally sensitive areas where they’re not allowed. Look up your destination on parks.wa.gov to make sure bud can accompany you on all parts of your state park getaway.

6 Tips for Hike Savvy Canines

Like house-bound humans, dogs need a little prep time to get ready for the trail. Here are six tips to help you and Fido have a safe and fun adventure.

#1 Take it Easy : Start with easy trails and slowly build up stamina & strength.

#2 Care for Tender Paws: Make sure your dog's pads are toughened or purchase hiking booties and let him get used to them before heading into the wild.

#3 Yield to oncoming traffic: No matter how sweet Fido appears, its good practice to verbalize how friendly he is. Step off the trail when hikers pass and heel your dog.

#4 Leash Control: If the trail requires leashes or if if your dog might run into other hikers, keep him on a short leash (-6') since a long leash is more likely to get tangled on brush. Your dog should not be allowed to roam freely.

#5 Leave no trace: Bring bags to collect and carry out your dog’s poop. If you’ll be backpacking overnight, bury it at least 6” deep and at least 200 ' from walkways, camps, and water sources.

#6 Command Ready: Hazards in the woods differ than the cul de sac. Don’t let your dog stray. Some plants are poisonous, and some creatures bite and may host diseases. Irressistable smells will lure pooch away in a flash. Make sure your obedience training is on track.

Visit backpacker.com for more ideas on a safe and rewarding journey!

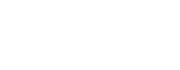

Taking Care of our stars

Starfish, or sea stars, are some of the ocean's most fascinating creatures. They lack brains and blood, digest food outside their bodies, and can regenerate lost limbs—sometimes even growing a new starfish from a single severed arm. In the colorful, thriving world of the Salish Sea, starfish stand out for their beauty and vital role in the ecosystem.

Text & images Thom Robbins

Starfish, or sea stars, are some of the ocean's most fascinating creatures. They lack brains and blood, digest food outside their bodies, and can regenerate lost limbs—sometimes even growing a new starfish from a single severed arm. In the colorful, thriving world of the Salish Sea, starfish stand out for their beauty and vital role in the ecosystem.

Beyond their striking appearance, starfish play a crucial role in maintaining balanced ecosystems. As keystone species, they regulate the populations of other marine animals, maintaining ecosystem balance. Without them, the entire system can become unbalanced, affecting many different species.

Starfish or Sea Stars?

While 'starfish' and 'sea star' are often used interchangeably, sea star is the scientifically accurate name. The reason is simple: sea stars are not actually fish. They lack scales, fins, and gills, which are essential characteristics of true fish. Regardless of this, 'starfish' remains the popular term in everyday language!

Diving into our local waters reveals a world of intricate ecological connections, with starfish acting as caretakers, maintaining the delicate balance of their underwater habitat.

One of everyone's favorites, the Ochre Sea Star, (shown above) with its vivid shades of purple, orange, and yellow, plays a crucial role in the Salish Sea. It's role of preying on oysters, mussels, and barnacles maintains an intertidal population balance and diverse marine ecosystem. Some aquaculture farmers may not agree, but without sea stars, oysters would dominate the habitat and disrupting the ecosystem balanc

30 Local Stars

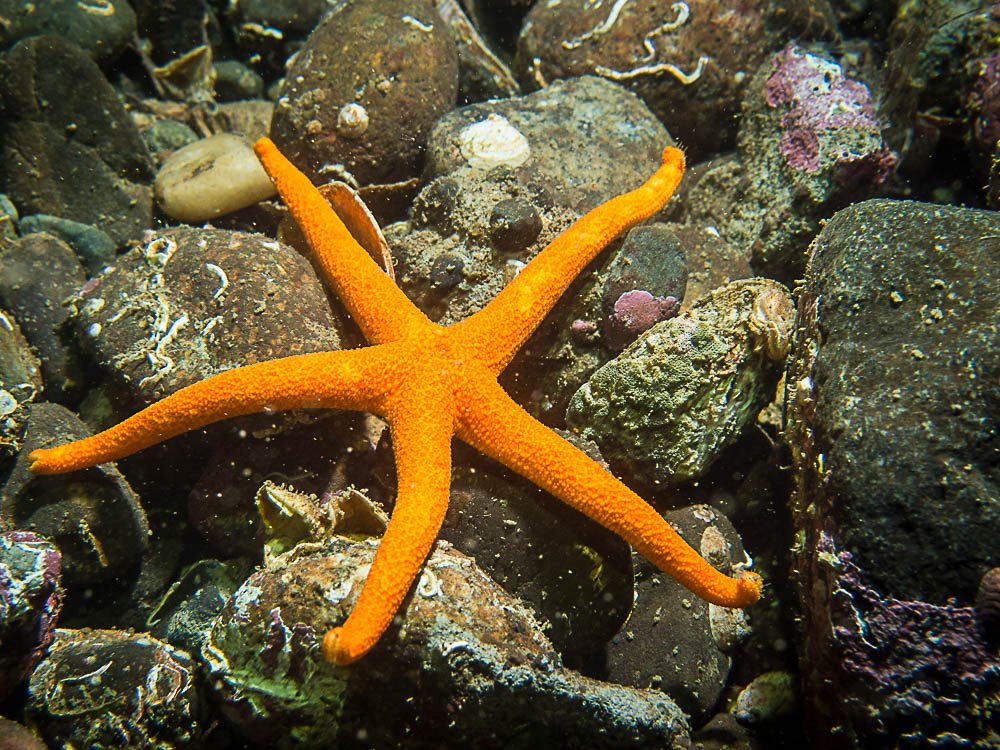

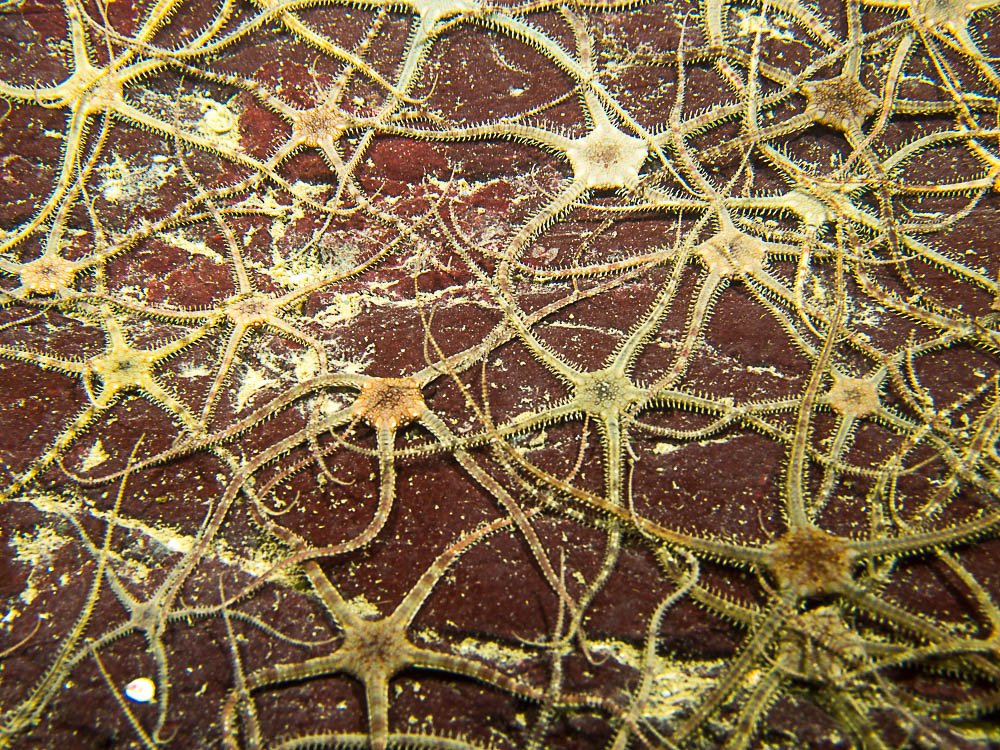

Of the 2,000 species worldwide, over 30 sea stars are found locally, adapted to the cool, nutrient-rich waters. This includes the vibrant Rainbow Star, known for its striking red and orange hues, often seen in rocky subtidal areas. This species is an active predator, feeding on urchins, snails, and even other starfish. Another intriguing species is the Vermilion Star, which inhabits deeper waters and stands out with its bright red hue. It primarily feeds on sponges and small invertebrates, slowly moving along the seafloor for prey.

Starfish belong to a diverse group of marine animals called echinoderms, which include sea urchins, sand dollars, and sea cucumbers. Echinoderms are characterized by radial symmetry, often with a five-point structure, though some species can have more arms. They also have unique skin, which ranges from smooth and velvety to spiny and rough. Their internal skeleton is made of calcium carbonate plates, giving them strength and flexibility.

Water for Blood

Instead of blood, sea stars pump seawater through a network of canals called the water vascular system. This system powers their movement, helps them breathe, and delivers nutrients throughout their bodies. By filtering seawater stars can absorb the oxygen and nutrients they need to survive.

By pumping seawater, they extend and retract tiny tube feet on their arms, which act like suction cups. This enables them to crawl across the ocean floor, clinging to rocks and rough surfaces. Some species do this surprisingly fast. the Sunflower Sea Star can travel up to a meter per minute!

Vermillion Star

Some sea stars use their suction-cup tube feet to pry open mussels, clams and oysters, exerting pressure with their tube feet up to ten times their body weight, giving them the power to open even the most tightly closed shells.

Once a starfish has pried open a shell just enough, it does something extraordinary—it extends its stomach out of its body and into the shell. This allows it to digest the prey externally, turning the meal into a liquid form that it can absorb into its body. This method of external digestion makes it easier for starfish to consume prey that would otherwise be too large to eat.

Each species has evolved distinct feeding strategies. For instance, the Leather Star has been known to drill tiny holes into the shells of its prey, providing access to hard-to-reach food sources.

A New Limb

One of the most fascinating features of starfish is their incredible ability to regenerate. Losing a limb isn’t the end for a starfish; it’s an opportunity for renewal. They can grow back a severed arm and, in some cases, even regenerate an entire body from just a part of a limb, as long as it includes part of the central disc.

This ability comes from specialized cells in their arms that can transform into the various types of cells needed for regrowth. This regenerative power helps them escape predators, heal from injuries, and even reproduce, making them incredibly resilient. Scientists are studying this ability not just to understand marine life better but also to explore its potential applications in medical research, offering new insights into how cells can regenerate and repair.

Each starfish species has adapted to thrive in its niche within the diverse marine environment. For instance, the Blood Star is well-suited to the cooler, deeper waters of the Pacific, where it feeds primarily on organic detritus and sponges. Unlike intertidal species, the Blood Star can be found on rocky reefs and sandy bottoms. Its bright red or orange coloration helps it stand out. Yet, it has developed the ability to blend into its surroundings when threatened, making it resilient and adaptable.

Deep-dwelling species like the Giant Pink Sea Star prefer the quiet, dark seabed. These starfish are found moving across the ocean floor, searching for prey like sponges and other slow-moving animals. The Velcro Star is known for its smooth, fluid movement. Their tube feet glide effortlessly over different surfaces in a coordinated, wave-like pattern. This technique lets it navigate tricky terrains, such as rocky crevices and dense kelp beds, with agility and speed. Its graceful movement, combined with a varied diet of algae, small invertebrates, and detritus, makes the Velcro Star highly adaptable across Pacific marine habitats.

The Bat Star, are often found in tide pools using their arms to sense the world around them. Each species has found a way to survive and thrive, whether braving the harsh intertidal zone, navigating the deep sea, or at home in tide pools.

Who needs a Brain?

Starfish have a decentralized nervous system rather than a central brain. This system consists of a nerve ring around their mouth, which connects to radial nerves running down each arm. Each arm acts independently, allowing the starfish to respond to its environment without a central control center.

The radial nerves help the starfish detect changes in temperature, light, touch, and the presence of chemicals in the water. Starfish may not have eyes like ours, but their keen sense of their surroundings helps them survive and thrive in a complex and sometimes harsh environment. Through research, conservation efforts, and sustainable practices, we may ensure that these celestial emblems of the ocean continue to thrive.

Starfish Lifecycle

The lifecycle of a starfish begins with species releasing vast clouds of sperm and eggs into the water, allowing fertilization to occur freely in the open sea. Once these eggs are hatched, starfish begin life as tiny, free-swimming larvae called bipinnaria. The larvae look nothing like their star-shaped adult selves. They resemble translucent creatures with cilia that help them move. Feed on microscopic plankton, life is perilous for these young starfish. They drift with the currents, exposed to predators and other dangers, with only a fraction progressing to the next development stage. They gradually transform into brachiolaria larvae, developing the first signs of the star-like body.

After months of drifting, the larvae transform dramatically, settling onto the seafloor and developing into juvenile starfish. This stage is crucial as they switch from a free-swimming lifestyle to one anchored to the ocean floor. Once settled, they start to look more like the familiar star-shaped adults, with their tube feet ready to help them move and search for food. Different species have their unique spawning behaviors. The Sunflower Sea Star, known for its speed and many arms, can produce thousands of eggs simultaneously, increasing the chances that some will survive despite the high predation risk. In contrast, the Leather Star releases fewer eggs throughout the season, spreading their reproductive efforts. Starfish have surprisingly long lifespan. The Red Sea Star lives up to 20 years. Their longevity allows them to play a vital role in maintaining the balance of their ecosystems. Each stage of their lifecycle, from tiny drifting larvae to powerful adult predators, is a testament to their resilience, intricately linked to the currents and tides.

Wasting Disease

Starfish wasting disease

Sea stars are adapted to withstand harsh conditions, like as pounding waves, intense heat, and dry low tides. However, during the 2014-2016 marine heatwave, ocean temperatures made them more susceptible to sea star wasting disease causing a populations decline from Mexico to Alaska. Sea star wasting disease (SSWD) is a condition that causes lesions, limb loss, and disintegration. It has been linked to Sea Star-associated Densovirus (SSaDV). Researchers have found higher concentrations of this virus in sick sea stars compared to healthy ones. The virus attacks their tissues, breaking down the body and spreading through shared habitats and even the water. This has been especially devastating for the Sunflower Sea Star. By 2021, it was estimated that up to 90% of the West Coast Sunflower Sea Star population were lost due to this disease. As a primary predators of sea urchins, their absence has led to a surge in urchin populations. Sea urchins began to overgraze kelp forests, resulting in "urchin barrens," areas where kelp has been decimated, leading to the loss of shelter and food for fish and invertebrates. This imbalance's ripple effects highlight how crucial sea stars are to maintaining a healthy ecosystem. Their decline affects the immediate species they prey on and can lead to broader shifts, impacting the entire marine food web. Researchers are exploring solutions including breeding disease-resistant sea stars. Some facilities have raised sea stars in captivity and released them into the wild, hoping to restore populations and introduce more resilient individuals. While challenges remain, efforts continue to understand this devastating disease.

As keystone species, starfish play a critical role in aquatic ecosystems. Today, starfish face numerous threats, from rising ocean temperatures and pollution to habitat loss and the spread of sea star wasting syndrome. Conservation efforts, such as breeding disease-resistant starfish and monitoring sea star health, are crucial to ensure these creatures continue to thrive.

Crossing the Bar - McMicken Island

There are no bridges or causeways to little McMicken Island in Case Inlet. No ferry service either. But you don’t need a kayak or boat to visit. You can easily hike to this island which lies about 0.2 mile off of the eastern shore of Harstine Island. It’s all in the timing.

Craig Romano | Story & images

There are no bridges or causeways to little McMicken Island in Case Inlet. No ferry service either. But you don’t need a kayak or boat to visit. You can easily hike to this island which lies about 0.2 mile off of the eastern shore of Harstine Island. It’s all in the timing.

When the tide is low, a tombolo (a sandbar connecting the island to the mainland—or in this case another island) is exposed allowing you dry foot access to the island. You then can hike the island’s small half mile trail, picnic in its small meadow, or explore big barnacle-encrusted rocks in its intertidal zone. Just mind the incoming tide lest you make a big splash on your island exodus.

Hit the Trail

The hike to little 11.5 acre McMicken Island begins from the 300-acre Harstine Island State Park. A former Washington DNR property, most of the old timber was logged off, but small groves of old-growth remains on the property.

You want to head to the park’s beach reachable by the two trails taking off south from the parking lot. Take the one on the eastern end of the lot (away from the kiosk) for the more direct route.

The trail heads towards Case Inlet soon reaching the edge of a 100 foot high forested bluff. Continue along the bluff taking in glimpses of the remote beach below. The way then descends into a cool and dark ravine graced with big cedars and firs and reaches a junction.

The trail to the right loops back to the other main trail leaving the parking lot. Consider taking it upon your return from McMicken Island.

Head left through a row of big cedars and via a series of steps descend deeper into the ravine. After crossing a little creek the way emerges on a deserted beach. Look directly across Case Inlet to Herron Island and the Key Peninsula. Then look south and spot McMicken Island set against a backdrop of big beautiful Mount Rainier. If the tide is high, you’ll have to wait to hike the beach as overhanging trees prohibit passage. But in a low tide, a big wide easy to walk beach awaits your footprints.

Walk for more than a mile undulating between cobbles, mud and sand. Watch for sand dollars scatted across the tide flats. Look too for eagles, herons and a myriad of seabirds. Harstine is a wet place and plenty of side creeks fan out on the beach. You should be able to keep your shoes dry, but a pair of waterproof boots is not a bad idea. The entire way to the tombolo is on public tidelands. But there is a parcel of private property located between two large state park properties abutting the shoreline. Respect posted private property.

The tombolo is pretty distinctive in low tides—fairly wide and several feet raised above inlet waters. In high tides it’s completely submerged, although breakers will help you locate its position. It’s really fun to hike it when a receding tide first reveals it. Tap your inner Moses and part the seas watching the land bridge emerge as you amble along it.

Reaching the island

Once across the .2 mile sandy strip, reach McMicken Island. All of the little island except for a small fenced parcel with a couple of cabins is state park property. The private holding belongs to the family that once owned the entire island. They sold the island to the state withholding this small lot. Please keep out of it. The rest of the island however you are free to explore.

At the island’s western end is a small picnic area in a grassy opening. Here find some rare Garry oaks growing on a low bluff above the surf. Near a composting toilet at the eastern edge of the field is a small nature trail. Hike it! It weaves a half mile through towering firs and madronas to blufftop views on the eastern end of the island.

Be sure to explore the rocky tide flats surrounding the island too, and check out the large erratics scattered about. There is a particularly large one on the south side of the island. Enjoy your island wanderings and explorations—more than likely sharing it with no more than just a couple of other happy hikers. And be sure to keep track of the time and incoming tide so you don’t get trapped on the island.

Places to Stay

Waterfront cabin located on Harstine Is with beach access and a panoramic view of the Puget Sound, Mt. Rainier and McMicken island. Check availability

Hike back to Harstine Island State Park and call it a day or consider walking some more. The park contains three miles of trails. They traverse thick fir forests and swampy cedar groves and are family and dog-friendly.

McMicken Island Notes:

Forest Setting with Beach Access

Cross the bridge to Harstine Is. and enjoy a beautiful and quiet retreat in the woods. Relax in the comfortably furnished cabin or enjoy exploring the 5 acre property with meandering trails through a lovely forest. Check availability

Distance: 4.0 miles round trip

Difficulty: easy, pay attention to tides! Hike is only possible in low tides. Consult tide tables and plan accordingly. Dogs permitted on leash.

Trailhead Pass Needed: Discover Pass

GPS Waypoints: Harstine Island State Park Trailhead: N47 15.737 W122 52.236 McMicken Island Trailhead: N47 14.865 W122 51.780

Features: Kid and dog friendly, beach hiking, undeveloped coastline, small island reached via a sandbar, good bird watching, sublime views of Mount Rainier over Case Inlet.

Trailhead directions: From Olympia, head north on US 101 to Olympic Highway (SR 3) Exit in Shelton. Then turn and follow SR 3 east for 11.0 miles. Turn right onto Pickering Road (Signed for Harstine Island) and drive 3.3 miles. Then bear left onto Harstine Bridge Road and come to a T-junction upon entering Harstine Island. Go left on North Island Drive and after 3.0 miles turn right at the island community hall onto East Harstine Island Road. Proceed for one mile and turn left onto Yates Road. Continue 0.9 mile and turn right into Harstine Island State Park. Reach trailhead parking in 0.2 mile.

A Hood Canal Road Trip

Ahh... road trips –there’s nothing that holds more appeal than the classic road trip – discovering new places, trying new things. Getting away from it all is as easy as heading to the South Sound via the Tacoma Narrows Bridge or by catching the Bremerton ferry for the 22 minute drive to Belfair, WA at the head of Hood Canal.

Ahh... road trips –there’s nothing that holds more appeal than the classic road trip – discovering new places, trying new things – Here's a sample itinerary to get you dreaming about discovering your adventures on Hood Canal.

Getting away from it all is as easy as heading to the South Sound via the Tacoma Narrows Bridge or by catching the Bremerton ferry for the drive to Belfair, at the head of Hood Canal.

Belfair, WA ( 22 minutes, 14 miles | Via SR 3 S)

Nestled between the North Bay of the Puget Sound and the southern hook of Hood Canal, Belfair is a great place for road trip supplies or to have lunch before heading off to explore the 130+ acre birder's dream wetlands, Theler Wetlands Nature Preserve. visit local craft brewery, Bent Bine Brew Co, to try their new brews. Hankering for wine? Check out the award winning Mosquito Fleet Winery, also calling Belfair home.

Twanoh State Park includes 3,167' of saltwater shoreline.

Twanoh State Park (14 minutes; 9.2 miles | via SR 106 W)

Twanoh State Park's 182 acres include 3,167 feet (965 m) of saltwater shoreline and 2.5 miles of inland hiking trails. Gather shellfish off the public beaches (when open) or simply take a walk on one of the many trails.

Alderbrook Resort & Spa (7 minutes, 5.2 miles | Via SR 106 W)

Since 1913, generations of visitors have enjoyed the rustic, albeit very luxurious, charm of this canal-side retreat on 88 acres, which include an 18-hole golf course. The 77 guest rooms are ideal for a rejuvenating escape, while the 16 cozy cottages are perfect for family fun. Complete with a waterfront restaurant, dock, and saltwater pool and spa, the Resort also offers access to boating from kayak rentals to multi-person cruises. Alderbrook Resort & Spa (Union, 10 E Alderbrook Dr, (360) 898-2200).

Union, WA (6 minutes, 2.4 miles | Via SR 106 W)

The spectacular views from Union are not to be taken lightly. Here is definitely the best vantage point to view the Olympic range. On the journey to Union's center, take a moment to admire the historic Dalby Water Wheel and stop in at Cameo Boutique for some great shopping of local items as well as the newly minted Hood Canale with a wood fire pizza and a spectaculr selection of wines. In Union check out the Union Country Store (5130 SR 106) for fresh bakery goods and all you need to continue on your adventure. Across the road, on the waterside, 2 Margaritas Restaurant serves Mexican food; while the Union City Market stocks everything from gifts and collectables to homemade candy and fresh oysters!

Hunter Farms (5 minutes, 3.4 miles | Via SR 106 W)

The drive along the Skokomish delta is simply perfect. As the road weaves it's path around the shoreline, you are treated to glimpses of the Olympics filtered through patches of arbutus clinging to the beach edge. Before the road forks west, you are greeted by an immense red barn. This is Hunter Farms. Stop and stretch your legs, check out the many animals and fresh produce as well as a selection of locally made products. Visit the onsite information kiosk –but most of all, get a generous cone filled with locally sourced (as in the Skokomish Valley less than 5 miles away!), Olympic Mountain Ice Cream. Amazing.

High Steel Bridge (26 minutes, 13 miles | Via W Skokomish Valley Rd

If you are up for a short diversion from the Hood Canal Loop, consider a trip to the historic High Steel Bridge that spans the gorge and sits a staggering 427’ above the mighty South Fork of the Skokomish River. Built in 1929, the vertigo-inducing Bridge (NF-2340) has an uncontested view of Vincent Creek Falls, and is easily accessed from Hwy 101. Use caution as the guardrails are decidedly short and the fall is a long way.

Potlatch, WA ( 5 minutes, 3.7 miles | Via WA-106 W and US-101 N)

Potlatch State Park is a 57-acre camping park with 9,570 feet of saltwater shoreline on Hood Canal. The park's grounds are home to a variety of activities, from interpretive programs for kids to boating and shellfish harvesting. Featuring clear, often calm waters, Potlach is a favorite with divers and kayakers, too.

Hoodsport, WA (5 minutes, 3.3 miles | Via US-101 N)

Hoodsport is a seaside town perched on the western shores of the Hood Canal beneath the shadow of the Olympic Range. Here you will find plenty of shops and dining as well as two wineries: Hoodsport Winery and Stottle Winery; as well as a distillery, The Hardware Distillery. Using water from the Olympic National Forest, The Hardware Distillery offers a variety of delectable hand crafted spirits and gorgeous view to enjoy while sipping away in their ambient tasting room. Hoodsport also serves as the gateway tp the Olympic National Park Staircase Entrance. At the foot of the hill, heading up to Lake Cushman, stop by the Hoodsport Information Center (N 150 Lake Cushman Rd) for great tips on road/trail conditions; permits and maps and friendly guidance.

Lilliwaup, WA ( 7 minutes, 4.5 miles | Via US-101 N)

Situated on the west shore of Hood Canal, Lilliwaup is a small town with a BIG history and a love of shellfish. Peppered with serene beaches and surrounded by endless hiking trails, Lilliwaup is all about relaxation and rejuvenation. Located in the area is Mike's Beach Resort. One of the oldest and most picturesque resorts in Hood Canal with a unique blend of the rustic look of the Northwest and the relaxed, cozy, and charming chalet style. A dock and mooring buoys as well as rowboats, paddleboat, and a ocean kayak are available for rent. Pet friendly. This is also the home to the Olympic Oyster Co. so you can be sure to enjoy some of the finest oysters on your stay! The Lilliwaup Store is also a great place to get your fill on Olympic Mountain Ice Cream.

Hama Hama Store and Oyster Saloon ( 8 minutes, 7 miles | Via US-101 N)

Family owned and operated, the Hama Hama Company has been harvesting oysters and clams on Hood Canal for four generations. Their store and outdoor restaurant, the Oyster Saloon, are located a shell’s-throw from the tide flats. A visit to the farm is the best way to experience Hood Canal oysters in their native habitat. Come during the week to see the shucking crew in action, and ask for one of their self guided tour maps to better explore the farm.

October is for Oysters in Mason County

With OysterFest the first weekend of October, we know its a great time to harvest oysters! Many of Washington’s public beaches are open year-round, and all you need is to check the tides and open beaches — grab your bucket, gloves, shucking knife, shellfish license, and head out to the local beach! As Jeff heads over to Verle's LLC to pick up his license and get tips on the best beaches to visit, join local harvesters Michael and Charlotte as they head to Hood Canal’s Eagle Creek beach to fill their frying pan and demonstrate shucking techniques and a quick and easy recipe for a beachside cookout! Can’t get any fresher!

With OysterFest the first weekend of October, we know it’s a great time to harvest oysters! Many of Washington’s public beaches are open year-round, and all you need is to check the tides and open beaches — grab your bucket, gloves, shucking knife, shellfish license, and head out to the local beach! As Jeff heads over to Verle's LLC to pick up his license and get tips on the best beaches to visit, join local harvesters Michael and Charlotte as they head to Hood Canal’s Eagle Creek beach to fill their frying pan and demonstrate shucking techniques and a quick and easy recipe for a beachside cookout! Can’t get any fresher!

The Top 5 | Camping on and around Hood Canal

Whether you prefer the simplicity of tent camping or the comfort of RVs there are plenty of campgrounds on and around the Hood Canal to choose from. From your campsite you can take day trips to explore surrounding forests, rivers, and beaches or just relax under the trees and listen to the birds.

Whether you prefer the simplicity of tent camping or the comfort of RVs there are plenty of campgrounds on and around the Hood Canal to choose from. From your campsite you can take day trips to explore surrounding forests, rivers, and beaches or just relax under the trees and listen to the birds. For some inspiration to plan your Summer trip to the Hood Canal the staff at Hood Canal Adventures have made up their list of top 5 favorite drive-in campgrounds.

The Top 5

#1 Collins Campground

Collins Campground is located within the U.S. National Forest in the Brinnon area. Nestled under giant Bigleaf Maple trees and directly on the Duckabush River, it contains only 16 sites with no-hook ups: and this is why we love it! From here you are within only a few miles from some of the areas most popular hiking trails including Murhut Falls, Ranger Hole and Duckabush Trail. Shellfish can be gathered nearby at the Duckabush or Dosewallips tidelands when the season is open for clam and oyster recreational harvests. The campground is first come / first served and is open mid-May through September. Visit fs.usda.gov or call the USFS Hood Canal Ranger District (360) 765-2200 for details.

#2 Seal Rock Campground

Seal Rock is another U.S. Forest Service campground in the Brinnon area, however this one is located directly on the Hood Canal with beach access. Forty-one tent and RV campsites are shaded beneath the evergreen trees, some with water views. There are no RV hook-ups but the campground does have fresh water, flush toilets and electricity in the restrooms. Oysters litter the beach at low tide for you to harvest and cook up over your campfire. The campground has an area to walk-in your small boat or kayak for exploring the Hood Canal or harvesting Dungeness and Red Rock crab. Hood Canal Adventures of Brinnon will deliver your kayaks, paddle boards, and crab pots if you choose to rent. Seal Rock Campground is first come / first served and open April through late September. Visit fs.usda.gov for details.

#3 Twanoh State Park

Twanoh State Park really has it all! Located on the southern end of the Hood Canal just outside Belfair, you’ll enjoy 22 full hook-up campsites and 25 tent sites, a pump-out station, boat launches and a dock, showers, covered picnic areas, group sites, a staffed park office and store, and even kayak rentals. Over 3,000 ft. of marine shoreline offers shell fishing opportunities and warm summer waters are perfect for swimming and water play. A few campsites are open all year but the beachfront area is open April through mid-October only. Twanoh State Park is first come / first served. Visit parks.state.wa.us or call 360-275-2222 for details.

#4 Potlatch State Park

Potlatch State Park is a 57-acre camping park with 9,570 feet of saltwater shoreline on Hood Canal. The park's beautiful grounds are home to a variety of activities, from interpretive programs for kids to boating and shellfish harvesting. The park has 19 tent spaces, 18 utility spaces, one dump station, one restroom and two showers. Sites have no hook-ups. Maximum site length is 60 feet (may have limited availability). Two of the tent sites are for primitive use (hikers and bicyclers) only. The Park is divided by Hwy 101 so choose sites that are further away from the road if possible.

#5 Lake Cushman

OK, this isn’t actually a campground but the Lake Cushman area is stunning and well worth exploring. Lake Cushman is located near Hoodsport between the Hood Canal and the Olympic Mountains. Its clear blue waters are framed by beautiful forests and snowy mountain peaks. Popular activities include fishing, hiking, climbing, boating, kayaking, and swimming. There are several campgrounds at the lake but we couldn’t agree as to which is our favorite. Therefore, here's a short list to start you off: Skokomish Park Lake Cushman with 80 RV, tent sites, boat launch, and lake access; Staircase Campground with 49 tent and RV sites on the Skokomish River at the Olympic National Park’s most southern access point; and Big Creek Campground, a 64 site U.S.F.S. Campground which also serves as the trail head to several hiking trails.

The Hood Canal area offers opportunities for camping whether they be county, state, federal, or private campgrounds. There are many back-country and boat-in only camping areas to explore. Come find your favorite! To discover more campgrounds in the area click here.

Christina Maloney is owner of Hood Canal Adventures in Brinnon, a Fisheries and Marine Biologist, and a local outdoor enthusiast.

Hundreds of varieties yet only five species | Oysters explained

There are over 150 varieties of oysters harvested and sold in North America, yet they comprise a total of only 5 species of oysters.

How does your Oyster Grow?

Have you ever wondered how the same species of oyster can have such varied flavors or textures? How does an oyster grown on Hood Canal taste brinier than one from South Puget Sound? The word to remember for your next oyster social occasion is “merrior.”

Like different wines with a “terrior,” oysters have a merrior, illustrating the fact that growing area and method make all the difference when it comes to flavor profile for your next Pacific oyster.

Not all beaches are created equal; some are muddy, some sandy, and some rocky. Each type of growing ground has opportunities and limitations for success. Muddy ground can inhibit the oysters’ ability to circulate water and food into their bodies. This had led to the adoption of culture techniques that suspend the oysters above the mud in long lines, stakes, nets or racks, and bags, while firm, sandy, or rocky bays allow for oysters to be grown right on the beach.

In addition to substrate type, location of the oysters on the beach will determine how long the oyster will take to achieve a marketable size. Oysters grown in the intertidal area are exposed to daily tidal inundation will have well developed adductor muscles and thicker shells thus being heartier for shipment. Oysters suspended in the water column for growing will have the benefit of a constant food source and thus grow quickly but will have delicate shells and be susceptible to the elements. Often times, suspended oysters are placed in the high energy intertidal environment for a few weeks prior to market to harden the shells for shipment and condition the oysters to hold their shells shut.

The method of growth can greatly change the shape of the oyster. A Pacific allowed to grow naturally on the beach will have a sturdy irregular shell with a great deal of frills. The regular exposure at low tide strengthens the shell protects the meat from heat and predators like sea stars and crabs. In Europe, where there is very limited tidal change, some farmers manually pull the oysters from the water for periods of time to mimic the tidal action.

The tumble bag creates an altered but very marketable shape for cultured oysters. Oysters are placed in the bag as small seed and the tide does the rest. The tidal flip and roll chip off the fragile lips and force the oyster to curve. The result is a deep cup in its lower shell.

“Eat shellfish to provide a healthy diet. Shellfish are low in saturated fats, containing the essential omega-3 fatty acids; are excellent protein sources; and are good sources of iron, zinc, copper and vitamin B-12.”

wsg.washington.edu

Each bay has its own selection of phytoplankton yielding oysters with different meat colors and flavors. Pacific oysters grown in Willapa Bay have a different merrior from those grown in Samish Bay. Hood Canal oysters are claimed to be more briny than the sweeter cucumber flavored bivalves grown in Hammersley Inlet or South Puget Sound waterways. Just like the well attuned vintners of the Rhone Valley, oyster connoisseurs are able to detect the subtleties of each bay by tasting the meat and observing the shell.

Know your oysters

There are over 150 varieties of oysters harvested and sold in North America, yet they comprise a total of only 5 species of oysters.

1. Olympia

OSTREA LURIDA /OSTREA CONCHAPHILA

The native oyster to Washington State, the Olympia oyster is a half dollar size with a metallic finish. The Olympia oyster fishery ran from the mid-1800s until about 1915 supplying California’s demand for oysters. The oysters were harvested from shallow bays of southern Puget Sound and Willapa Bay until pollution and over harvesting caused a collapse of the wild fishery.

2. Pacific

CRASSOSTREA GIGAS

Native to Japan, farmers began experimenting with the Pacific in 1904. Washington began importing commercial seed in the 1930’s and now it is now the most important commercial species on the West Coast. Beginning in the 1950’s researchers began to study Pacific reproduction to reduce the dependence on seed imports. Since the 1970’s local shellfish growers have relied on hatcheries for the production to meet the demand for Northwest oysters.

3. Virginica

CRASSOSTREA VIRGINICA

The decline of the Olympia oyster opened the door for the import of the Virginica from the east coast in the early 1900’s. The eastern oysters did not adapt well to local waters and experienced large die off when transplanted. There are still beds of Virginicas raised by WA shellfish farmers.

4. European Flats

OSTREA EDULIS

European Flats have smooth, round, saucer-like, flat shells with a shallow cup and seaweed-green color. They have a bold flavor with a meaty, almost crunchy texture, and intense mineral bite with a long-lasting seaweed flavor and gamey finish. There are not many farmers cultivating Flats.

5. Kumamoto

CRASSOSTREA SIKAMEA

The Kumamoto has a small deep cup and a sweet meat. Brought from Japan’s Kumamoto Prefecture, they are unable to reproduce in our cold waters so growers rely on hatchery stock. The prized cup of the Kumamoto and its limited supply has growers working with Pacifics to meet half shell demands. Growers use tumble bags to force the Pacific into a deeper cup. Oysters with names such as Kusshi, Shigoku, Sea Cow, Blue Pools, Chelsea Gems, and Baywater Sweets, are the result.

Why is it required to shuck oysters on the beach at public tidelands?

Oysters taken on public tidelands must be shucked on the beach and the shells left behind for the following conservation-based reasons according to the Washington Dept of Fish & Wildlife website, wdfw.wa.gov:

Oyster shells provide the best growing substrate for juvenile oysters. Removing the shells from a beach reduces the overall amount of setting surface. In addition, Pacific oyster shell provides an excellent setting surface for the native Olympia oyster. This is especially true in places like southern Puget Sound where the natural setting surface - Olympia oyster shells - was eliminated years ago by overharvest.