THE STILL ONES: LIFE AMONG PACIFIC NORTHWEST ANEMONES

STORY & IMAGES: THOM ROBBINS

H/T Tracing The Fjord | Winter ‘25

Drop beneath the surface of Hood Canal, and the world does something strange. The noise you never realized you carried slips away. The cold presses close, the green water folds around you, and what felt familiar on the surface becomes something older, slower, more deliberate. Down here, even the smallest things can pull your attention, and few creatures lure you in like anemones.

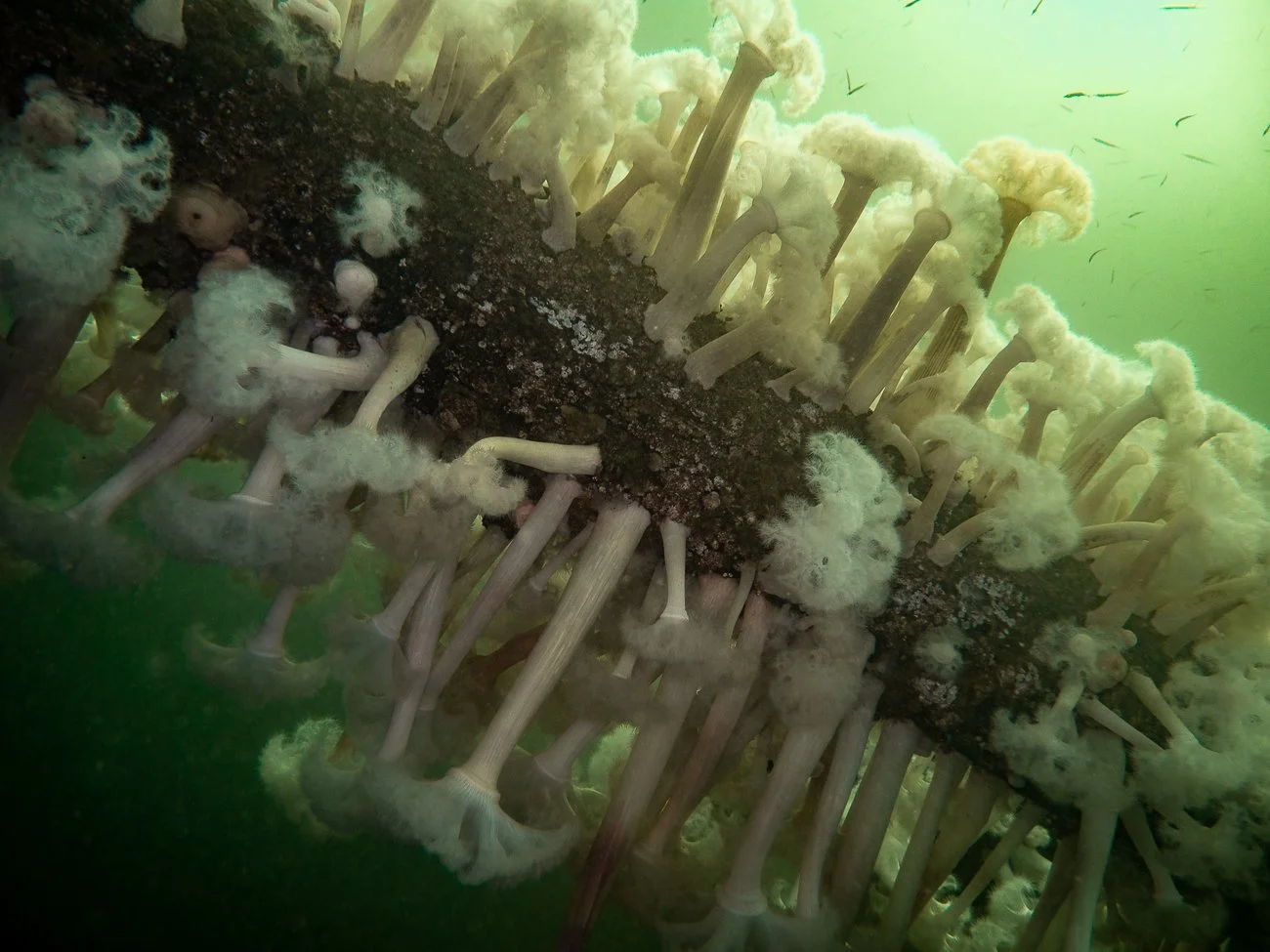

The first time I hovered eye-level with a pair of orange-and-white plumose anemones, anchored together, I realized I’d stopped breathing. They rose from the rock like a lantern someone forgot to snuff out, their feathery rings swaying with the patience of something that had never once needed to rush. I had dropped into the water that day looking for wolf eels, maybe a wandering Pacific octopus if I was lucky, but instead I found myself suspended in the water, staring at a creature that held the whole moment in its grip.

The light from my dive torch slid across its surface, and the anemone flared gently, as if waking. The muted fire of orange and white felt older than anything else on the reef. I stayed there longer than I meant to, caught by something anchored in place, looking back without eyes and waiting without fear.

People often imagine anemones as simple flowers of the sea. They are anything but. Spend enough time underwater with them and you see the truth: they are predators, architects, survivors, and quiet powerhouses of the Pacific Northwest. They feed the ecosystem, help shape the seafloor, and provide shelter for everything from tiny shrimp to juvenile rockfish.

And they manage all of this without ever taking a single step.

Up close, anemones feel uncanny in a way only the sea manages—rooted creatures that still seem alert and watching. Divers tend to lump them together, these bright creatures pinned to the rocks, but the truth is far older and stranger than it appears. They all belong to the same ancient lineage, the class Anthozoa, animals that appeared long before fish, long before bones, long before anything with a face to show its intent.

Each anemone follows a familiar blueprint: a soft column crowned with tentacles and anchored by a disc. That disc holds the animal to rock, piling, sand, or shell and lets it ride out currents that could peel skin from stone. For a few species, it even becomes a getaway tool. When conditions turn bad, some Pacific Northwest anemones release their grip, inflate slightly, and drift away like pale balloons searching for safer ground.

Stillness is their choice, not their limitation.

In the Pacific Northwest alone, there are several dozen species of sea anemones. Within that shared design, each species holds its own personality, its own way of surviving a world that rarely shows mercy. Some anemones are patient hunters, waiting for fish or shrimp to brush against their tentacles so their stinging cells can fire like tiny traps tucked inside a single hair. Others are filter feeders, living a life where the current does the work, sweeping plankton across their tentacles. A few do both, depending on what the tides bring, switching strategies the way a writer changes pens—steady and deliberate.

Some swallow crabs whole. Others feed on jellies. Some are as small as scattered beads on the rock, and others rise tall enough to brush a diver’s mask.

They are family in the scientific sense, but in the water, they feel more like estranged relatives gathered in the rooms of the same old house. They share the same history, but each carries its own hidden secrets. Some shimmer with light borrowed from algae living inside them. Others wage quiet chemical war against their neighbors.

A few clone themselves into armies that spread across the seafloor like a slow tide. Others, despite their rooted appearance, quietly unstick and sail off into the dark if the world around them shifts.

They may look decorative at first, but spend enough time with them and the illusion dissolves. Beneath the calm is intention. Beneath the color is strategy. And beneath the soft drift of tentacles is a creature that has been perfecting survival since before the ocean knew anything more complicated than hunger and light.

Once you start paying attention, their structure begins to make sense through function rather than form. At the top, the tentacles guard a single opening that leads into the coelenteron, the chamber where circulation, digestion, and waste share a common path. There is no heart or specialized organs, only water moving through the body to do the work. It is simple on the surface and efficient beneath, a design nature created early and never had reason to revise.

If you understand that basic framework, the distinctions between species sharpen, almost like personalities rather than anatomy.

Giant green anemones are usually the first to pull you in, their bodies lit from within as if they are holding on to every bit of sunlight they ever borrowed. The color runs deeper than the tissue because of the algae living inside their cells, tiny partners trading photosynthesis for shelter. Brush too close and the whole ring of tentacles snaps shut, quick and certain, a reflex shaped by millions of years of ambush. To us, the sting is little more than a pinprick. To anything small enough to count as prey, it is a door shutting for good.

Plumose anemones follow the same plan but stretch it into something ghostly. They rise from pilings and rocky shelves as pale towers, their feathery tentacles blooming under a dive light. They do not hunt so much as gather. They stand in the current and let the world pass through their arms, sifting plankton with steady ease. On night dives, they look like candles lining some forgotten aisle, pale glimmers flickering each time a tide pulse rolls through. I have floated among them with only my breath for company and felt, for a moment, that I had wandered someplace sacred and not entirely safe.

Painted anemones carry the same architecture but disguise it under carnival colors. Reds, purples, creams, and browns swirl across their columns, so vivid you almost doubt what you see through your mask. They hold perfectly still, predators that know stillness can be its own kind of lure. I once watched a hermit crab inch across the edge of a painted anemone, as if easing across ice that might crack beneath it. One careless touch, one stumble into the tentacles, and that would have been the end of him. The anemone never twitched. It didn’t need to. Time does the work.

Then there are the aggregating, or clonal, anemones, the most abundant anemones on the tide-swept rocky shores of the Pacific coast. They repeat their small green design across whole stretches of reef, shrinking the instant a finger or wave brushes them. Most people never realize these harmless-looking colonies wage slow territorial wars, leaving chemical borders etched into the rock long after the fighting has ended.

And in the dimmer reaches of the walls, you find the strawberries—small and intensely bright, gathered in clusters that shine like embers against the rock. Their red and pink tones come from pigments in their own tissues, natural shields that help them handle shifting light rather than anything they eat. A single anemone barely catches the eye, but together they form tiny reefs, pockets of shelter where young fish slip out of the current. Shrimp thread themselves between the bodies, and tiny crabs wait out storms beneath the guarded crowns, trusting something that looks delicate yet stays anchored through anything the water delivers.

That is the truth anemones keep tucked beneath their soft crowns. They look like decoration, the ocean’s wildflowers, but nothing could be more wrong. They are shelter and glue, hunters and architects, patient predators and caretakers. They build structure where none would stand. They root the ecosystem in place. Without them, parts of Hood Canal would feel hollow in ways you only understand after you have spent years underwater, watching the quiet power of creatures that never move and never need to.

They are not background. They are the bones around which the seafloor grows.

For something anchored in place, anemones live complicated lives. They begin as drifting larvae, tiny specks carried wherever the tides push them. Most never make it, swept off or swallowed long before they touch stone. The few that survive settle on a rock, shell, piling, or even an old bottle and anchor there. Once they attach, they stay for life, which can stretch for decades if the currents and predators leave them be.

Once settled, anemones grow slowly and steadily, unfurling their tentacles to hunt. Those tentacles are loaded with tiny stinging cells called nematocysts. Under a microscope, they look like harpoons coiled in a trap, waiting for anything soft enough to touch.

Here’s a quiet bit of trivia: the same stinging machinery that makes box jellies deadly exists in Pacific Northwest anemones. Ours are far gentler, but the machinery is the same—just scaled down.

Some reproduce sexually by releasing eggs and sperm into the water, letting the current handle the matchmaking. Others, like aggregating anemones, clone themselves until an entire colony becomes one genetic individual. Kneel beside one and you might be looking at hundreds of copies of a single ancestor.

It’s an ancient strategy, and it works.

Underwater, alliances are messy, and enemies show up in strange shapes. Small crabs hide beneath anemones. Shrimp thread between their tentacles. Juvenile rockfish hover above them like nervous birds perched on an unseen rail. Anemones are living real estate, shelter for whatever needs protection from the current or from things waiting to strike.

Some fish even learn to hover close enough to avoid predators but not so close that they get stung. It’s an uneasy arrangement, but down here, even bad roommates can get along if the alternative is being eaten.

Crabs, strangely enough, are both protected by and prey to anemones. I have watched decorator crabs tiptoe across their tentacles with scraps of sponge strapped to their backs like makeshift armor. They move with a careful, testing gait, feeling for the slightest hint of danger. Sea stars sometimes pry anemones off rocks, consuming them in slow, patient mouthfuls. It is not a quick process. Nothing underwater ever is quick.

And then there are the battles you never see, the chemical duels between neighboring colonies. Aggregating anemones have specialized “fighter” polyps that they use to burn competitors. The line between territories is drawn in sting scars. Some anemones even fight themselves by accident, clone battling clone after currents shift them into the wrong arrangement.

Everything in the ocean is friend, enemy, or dinner. Sometimes it is all three at once.

If you ever want to understand the Pacific Northwest, descend into Hood Canal when the water turns green and the current softens. Look for the places where color gathers on the stone. Where tiny tentacles reach and sway. Where something motionless begins to feel like it is breathing with the sea.

Anemones are easy to overlook, but once you notice them, they pull you in. They are the quiet machinery of the ecosystem, visible only when you slow down enough to see them. They filter water, provide habitat, feed predators, and shape entire stretches of shore with time and patience.

On one late-winter dive, I found a single giant green anemone perched on a rock, its tentacles half-closed against the surge. I hovered there, just watching it. A whole world moving around a creature that stayed fixed in place. I raised my camera, took the shot, and realized something simple.

Not every marvel in the Salish Sea chases you or darts across your light, trying to be seen. Some simply wait to be noticed. And once you do, you begin to see the seafloor differently. You understand how much depends on what stays still.

THOM ROBBINS BIO

I spend as much time underwater as life allows, teaching diving and photography, chasing the perfect shot, and writing both nonfiction and fiction inspired by these waters. You can explore more of my work at www.thomrobbins.com.