BIRDS OF A FEATHER FLOCK TOGETHER

Birding in the Pacific Northwest is more than checklists and binoculars. From wetlands and estuaries to forest trails along Hood Canal, this guide explores how modern birding blends technology, community, and quiet observation—highlighting local places in Mason County where birds and birders naturally gather.

H/T Tracing The Fjord | Winter ‘25 | STELLA WENSTOB | olympicbirdtrail.com

Those folks obsessed with bird identification? Yes, birders—and they’re far cooler than the stereotype suggests.

Once caricatured as binocular-toting nerds with overstuffed packs and dubious dried banana chips, today’s birders are more likely carrying a smartphone than a color-coded guidebook. Nerdy, it turns out, is in. Modern birding trades paper for sleek apps like iBird and iNaturalist, making it easy to identify, log, and even crowdsource sightings—all while contributing to real scientific understanding.

In the Pacific Northwest, with its remarkable variety of birdlife, birding is about far more than snacks and checklists. It’s an inviting way to slow down, look up, and connect with the natural world.

Getting Started

The Audubon Society is a great place to start if you’re just dipping your webbed foot into the vast waters of birding. Their website offers a free birding app, engaging articles, and access to hundreds of local chapters—five in the Olympic-Kitsap Peninsula area alone—that host birding classes, walks, and events.

One of those events is the longest-running bird census in the world: the Christmas Bird Count. Now entering its 125th year, the count gathers data from volunteer birders across North and South America. It was developed as a replacement for the old holiday “side hunt,” a competitive tradition among hunters that focused on the most game taken over the season.

Learning From the Nest

If the weather is too nasty to head outside, stay in your nest and feather it with avian knowledge. The Audubon Society offers online courses, including interactive Zoom lectures with local experts. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology provides more in-depth, accredited bird identification courses, along with plenty of solid free basics.

The Washington Ornithological Society and American Birding Association also offer a digital, up-to-date version of A Birder’s Guide to Washington. While it doesn’t help with identification, it provides an exhaustive list of where to find species and helps plan productive birding adventures.

Birding Mason County

If you’re ready to venture out in wintery weather, Mason County is teeming with migratory and year-round resident birds. Hit the trails and start scanning the skies, vegetation, and waterways.

Pack binoculars, a scope, digital camera, or smartphone (with iBird and Audubon maps downloaded). Old-school works too—just a notepad and pencil. Wear good walking shoes and weather-appropriate clothing.

Almost every green space—backyard or state park—offers birding potential. To honor the spirit of road trips and the hallowed practice of list-making, here are a few favorite local birding haunts.

For the Birds

Hilburn Preserve

The Capitol Land Trust Hilburn Preserve, just off Highway 101 west of Shelton, features an easy half-mile loop beside the lively Goldsborough Creek. The wooded habitat is ideal for spotting woodland birds such as Red-breasted Sapsucker, Hutton’s Vireo, Pacific Wren, and Cedar Waxwing.

Bayshore Preserve

Leaving Hilburn, head east on Railroad Avenue toward downtown Shelton, then north on Olympic Highway South. Turn right onto Highway 3 (East Pine Street), which follows Oakland Bay to the Bayshore Preserve.

This Capitol Land Trust property is part of the Great Washington State Birding Trail. Oak savannas border the shoreline and Johns Creek outflow. Peregrine Falcons have been spotted perched in the oaks, while Great Blue Herons frequent the open areas. Scan the bay for waterfowl diving in warmer waters.

Mary Theler Wetlands Nature Preserve

Located just outside Belfair (22641 WA-3), this 139-acre preserve protects estuarine habitat along the Union River delta. Marshlands, meadows, forests, and tidal waters support impressive wildlife diversity.

Five trails highlight different habitats, some with views of the southern Olympic Mountains. The River Estuary Trail—built atop breached dikes—offers sightings of river otters, Belted Kingfishers, and Great Blue Herons. Pools host Northern Pintail, Green-winged Teal, Common Merganser, and a wide range of shorebirds. Bald Eagles are commonly seen.

Twanoh State Park & Skokomish River Delta

Backtrack along Highway 106 toward Hood Canal to reach Twanoh State Park. With over 182 acres of forest and shoreline, it offers both terrestrial and marine birding. The 2.5-mile inland trail is reliable for Red Crossbills and Brown Creepers.

Continuing through Union brings you to the Skokomish River delta, rich with waterfowl such as Mallard, Northern Pintail, Red-breasted Merganser, and large flocks of American Wigeon. Bald Eagles are frequent here.

Hood Canal Corridor

Heading north on Highway 101 keeps you alongside Hood Canal, with strong birding stops at Potlatch State Park, Lilliwaup Creek, Eagle Creek, and Jorsted Creek.

At Jorsted Creek, pilings from an old log dump serve as roosts for all three species of cormorants. Lacking water-repellent oils, these birds are often seen perched with wings spread to dry.

The Hamma Hamma River estuary is another productive area and home to a nearby Great Blue Heron rookery.

Dosewallips State Park

The final stop on this list, Dosewallips State Park spans more than 1,000 acres of river, estuary, shoreline, and mature forest. Known for Roosevelt Elk and curious seals offshore, it also supports a wide range of bird species.

The North Tidal Trail crosses marshes and offers excellent winter views of migrating Trumpeter Swans.

The parks and preserves of the Pacific Northwest offer outstanding birding opportunities. Birds of a feather flock together—and birders are never far behind.

For more information on fjord birding, visit olympicbirdtrail.com.

A Winter Guide to Our Local Tides

In winter, the tides along Hood Canal feel different. King tides push water higher than usual, low tides arrive before daylight, and currents move faster through familiar stretches of shoreline. Knowing how and why these tides shift can make winter outings safer and more rewarding.

H/T Tracing The Fjord | Winter ‘25

If you live or spend any time along Hood Canal or in the South Sound, you get used to checking the tides. They shape when people head out for recreation, plan a boat launch, or keep an eye on their waterfront. But the names we use for tides can feel a little mysterious until you break them down.

Tides are the rise and fall of the ocean caused by the gravitational pull of the moon and the sun. As the Earth turns, our area passes through these gravitational pulls, which is what causes the highs and lows we notice along the shoreline. Most of the Pacific Coast, including Hood Canal and South Puget Sound, experiences what’s called mixed semi-diurnal tides, meaning two highs and two lows every 24 hours. Still, each one is a little different in height. Regular tide-chart watchers recognize that pattern right away.

You’ll also hear terms like spring tides and neap tides. Spring tides aren’t tied to the season. They happen when the sun, moon, and Earth line up, which creates higher highs and lower lows. Neap tides are the opposite. They arrive when the sun and moon are at right angles to each other, pulling the water in different directions and producing milder highs and lows.

Another term that comes up often in winter is king tide. It’s not a scientific label, but a common nickname for the year’s highest tides. These happen when the moon is closest to Earth and lines up with the sun. Around Hood Canal, king tides can raise water levels several feet above normal. People may notice when the shoreline creeps inland and low-lying roads collect water.

In winter, tide shifts carry a different rhythm. Many of the lowest tides show up in the early morning or evening, long before daylight. Boaters and paddlers will see water levels changing faster through the Great Bend or around Ayock Point. Homeowners might keep an eye on their docks and pilings, since deep lows can expose more structure than usual.

Shellfish growers around the canal monitor winter tides too, since cold air paired with low water can stress their crops. And for anyone heading out to collect shellfish on local beaches, those low tides can be inviting—just make sure you have the proper license and check harvest openings before you go.

A better understanding of the tides helps explain what we see every day along the Canal. And for anyone heading out in the winter months, a quick tide check remains one of the easiest ways to stay safe and make the most of the season.

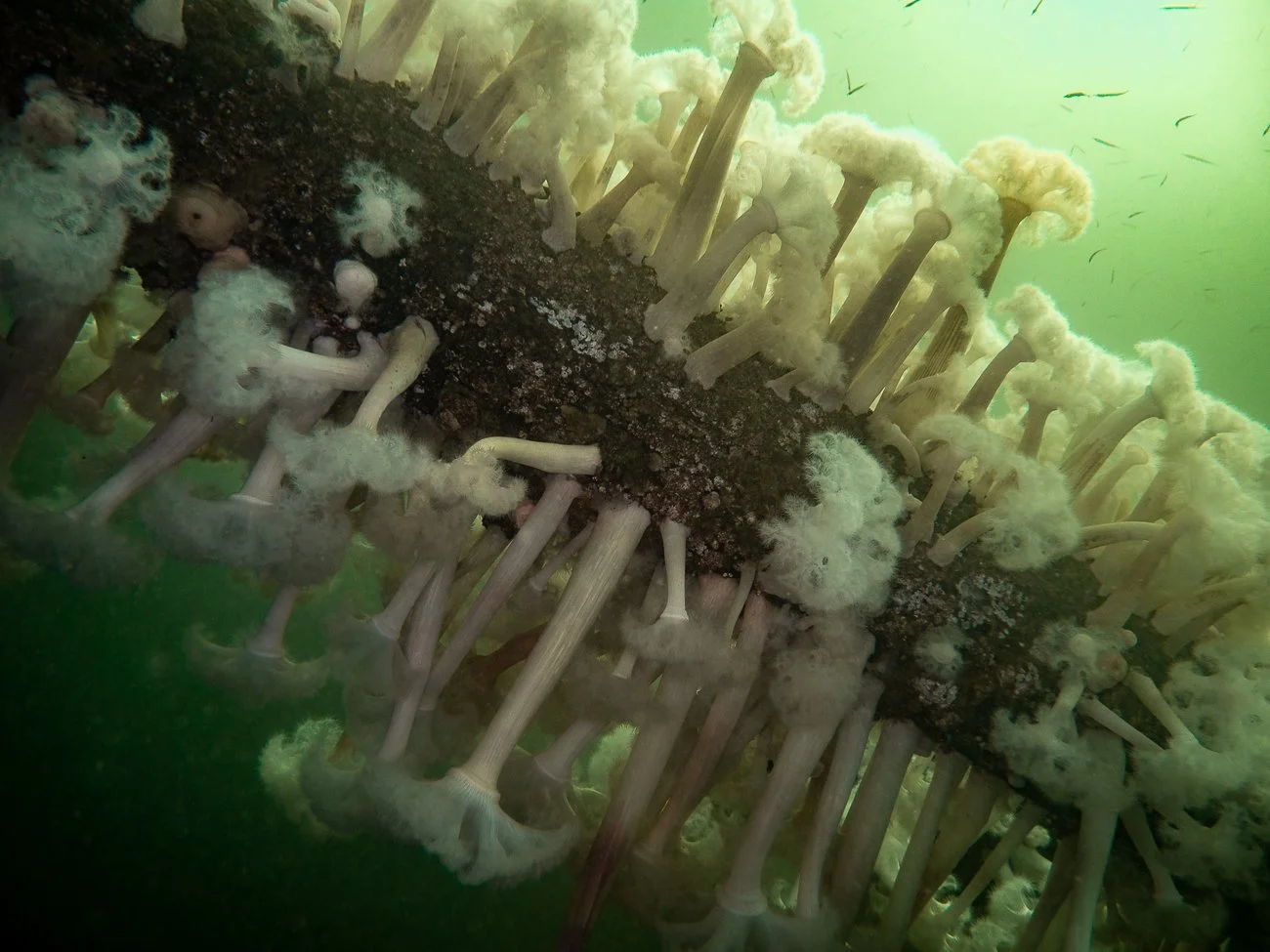

THE STILL ONES: LIFE AMONG PACIFIC NORTHWEST ANEMONES

Drop beneath the surface of Hood Canal and the noise of the surface fades away. In the cold green water, sea anemones reveal themselves not as simple flowers, but as hunters, shelter, and the steady framework of the underwater world.

STORY & IMAGES: THOM ROBBINS

H/T Tracing The Fjord | Winter ‘25

Drop beneath the surface of Hood Canal, and the world does something strange. The noise you never realized you carried slips away. The cold presses close, the green water folds around you, and what felt familiar on the surface becomes something older, slower, more deliberate. Down here, even the smallest things can pull your attention, and few creatures lure you in like anemones.

The first time I hovered eye-level with a pair of orange-and-white plumose anemones, anchored together, I realized I’d stopped breathing. They rose from the rock like a lantern someone forgot to snuff out, their feathery rings swaying with the patience of something that had never once needed to rush. I had dropped into the water that day looking for wolf eels, maybe a wandering Pacific octopus if I was lucky, but instead I found myself suspended in the water, staring at a creature that held the whole moment in its grip.

The light from my dive torch slid across its surface, and the anemone flared gently, as if waking. The muted fire of orange and white felt older than anything else on the reef. I stayed there longer than I meant to, caught by something anchored in place, looking back without eyes and waiting without fear.

People often imagine anemones as simple flowers of the sea. They are anything but. Spend enough time underwater with them and you see the truth: they are predators, architects, survivors, and quiet powerhouses of the Pacific Northwest. They feed the ecosystem, help shape the seafloor, and provide shelter for everything from tiny shrimp to juvenile rockfish.

And they manage all of this without ever taking a single step.

Up close, anemones feel uncanny in a way only the sea manages—rooted creatures that still seem alert and watching. Divers tend to lump them together, these bright creatures pinned to the rocks, but the truth is far older and stranger than it appears. They all belong to the same ancient lineage, the class Anthozoa, animals that appeared long before fish, long before bones, long before anything with a face to show its intent.

Each anemone follows a familiar blueprint: a soft column crowned with tentacles and anchored by a disc. That disc holds the animal to rock, piling, sand, or shell and lets it ride out currents that could peel skin from stone. For a few species, it even becomes a getaway tool. When conditions turn bad, some Pacific Northwest anemones release their grip, inflate slightly, and drift away like pale balloons searching for safer ground.

Stillness is their choice, not their limitation.

In the Pacific Northwest alone, there are several dozen species of sea anemones. Within that shared design, each species holds its own personality, its own way of surviving a world that rarely shows mercy. Some anemones are patient hunters, waiting for fish or shrimp to brush against their tentacles so their stinging cells can fire like tiny traps tucked inside a single hair. Others are filter feeders, living a life where the current does the work, sweeping plankton across their tentacles. A few do both, depending on what the tides bring, switching strategies the way a writer changes pens—steady and deliberate.

Some swallow crabs whole. Others feed on jellies. Some are as small as scattered beads on the rock, and others rise tall enough to brush a diver’s mask.

They are family in the scientific sense, but in the water, they feel more like estranged relatives gathered in the rooms of the same old house. They share the same history, but each carries its own hidden secrets. Some shimmer with light borrowed from algae living inside them. Others wage quiet chemical war against their neighbors.

A few clone themselves into armies that spread across the seafloor like a slow tide. Others, despite their rooted appearance, quietly unstick and sail off into the dark if the world around them shifts.

They may look decorative at first, but spend enough time with them and the illusion dissolves. Beneath the calm is intention. Beneath the color is strategy. And beneath the soft drift of tentacles is a creature that has been perfecting survival since before the ocean knew anything more complicated than hunger and light.

Once you start paying attention, their structure begins to make sense through function rather than form. At the top, the tentacles guard a single opening that leads into the coelenteron, the chamber where circulation, digestion, and waste share a common path. There is no heart or specialized organs, only water moving through the body to do the work. It is simple on the surface and efficient beneath, a design nature created early and never had reason to revise.

If you understand that basic framework, the distinctions between species sharpen, almost like personalities rather than anatomy.

Giant green anemones are usually the first to pull you in, their bodies lit from within as if they are holding on to every bit of sunlight they ever borrowed. The color runs deeper than the tissue because of the algae living inside their cells, tiny partners trading photosynthesis for shelter. Brush too close and the whole ring of tentacles snaps shut, quick and certain, a reflex shaped by millions of years of ambush. To us, the sting is little more than a pinprick. To anything small enough to count as prey, it is a door shutting for good.

Plumose anemones follow the same plan but stretch it into something ghostly. They rise from pilings and rocky shelves as pale towers, their feathery tentacles blooming under a dive light. They do not hunt so much as gather. They stand in the current and let the world pass through their arms, sifting plankton with steady ease. On night dives, they look like candles lining some forgotten aisle, pale glimmers flickering each time a tide pulse rolls through. I have floated among them with only my breath for company and felt, for a moment, that I had wandered someplace sacred and not entirely safe.

Painted anemones carry the same architecture but disguise it under carnival colors. Reds, purples, creams, and browns swirl across their columns, so vivid you almost doubt what you see through your mask. They hold perfectly still, predators that know stillness can be its own kind of lure. I once watched a hermit crab inch across the edge of a painted anemone, as if easing across ice that might crack beneath it. One careless touch, one stumble into the tentacles, and that would have been the end of him. The anemone never twitched. It didn’t need to. Time does the work.

Then there are the aggregating, or clonal, anemones, the most abundant anemones on the tide-swept rocky shores of the Pacific coast. They repeat their small green design across whole stretches of reef, shrinking the instant a finger or wave brushes them. Most people never realize these harmless-looking colonies wage slow territorial wars, leaving chemical borders etched into the rock long after the fighting has ended.

And in the dimmer reaches of the walls, you find the strawberries—small and intensely bright, gathered in clusters that shine like embers against the rock. Their red and pink tones come from pigments in their own tissues, natural shields that help them handle shifting light rather than anything they eat. A single anemone barely catches the eye, but together they form tiny reefs, pockets of shelter where young fish slip out of the current. Shrimp thread themselves between the bodies, and tiny crabs wait out storms beneath the guarded crowns, trusting something that looks delicate yet stays anchored through anything the water delivers.

That is the truth anemones keep tucked beneath their soft crowns. They look like decoration, the ocean’s wildflowers, but nothing could be more wrong. They are shelter and glue, hunters and architects, patient predators and caretakers. They build structure where none would stand. They root the ecosystem in place. Without them, parts of Hood Canal would feel hollow in ways you only understand after you have spent years underwater, watching the quiet power of creatures that never move and never need to.

They are not background. They are the bones around which the seafloor grows.

For something anchored in place, anemones live complicated lives. They begin as drifting larvae, tiny specks carried wherever the tides push them. Most never make it, swept off or swallowed long before they touch stone. The few that survive settle on a rock, shell, piling, or even an old bottle and anchor there. Once they attach, they stay for life, which can stretch for decades if the currents and predators leave them be.

Once settled, anemones grow slowly and steadily, unfurling their tentacles to hunt. Those tentacles are loaded with tiny stinging cells called nematocysts. Under a microscope, they look like harpoons coiled in a trap, waiting for anything soft enough to touch.

Here’s a quiet bit of trivia: the same stinging machinery that makes box jellies deadly exists in Pacific Northwest anemones. Ours are far gentler, but the machinery is the same—just scaled down.

Some reproduce sexually by releasing eggs and sperm into the water, letting the current handle the matchmaking. Others, like aggregating anemones, clone themselves until an entire colony becomes one genetic individual. Kneel beside one and you might be looking at hundreds of copies of a single ancestor.

It’s an ancient strategy, and it works.

Underwater, alliances are messy, and enemies show up in strange shapes. Small crabs hide beneath anemones. Shrimp thread between their tentacles. Juvenile rockfish hover above them like nervous birds perched on an unseen rail. Anemones are living real estate, shelter for whatever needs protection from the current or from things waiting to strike.

Some fish even learn to hover close enough to avoid predators but not so close that they get stung. It’s an uneasy arrangement, but down here, even bad roommates can get along if the alternative is being eaten.

Crabs, strangely enough, are both protected by and prey to anemones. I have watched decorator crabs tiptoe across their tentacles with scraps of sponge strapped to their backs like makeshift armor. They move with a careful, testing gait, feeling for the slightest hint of danger. Sea stars sometimes pry anemones off rocks, consuming them in slow, patient mouthfuls. It is not a quick process. Nothing underwater ever is quick.

And then there are the battles you never see, the chemical duels between neighboring colonies. Aggregating anemones have specialized “fighter” polyps that they use to burn competitors. The line between territories is drawn in sting scars. Some anemones even fight themselves by accident, clone battling clone after currents shift them into the wrong arrangement.

Everything in the ocean is friend, enemy, or dinner. Sometimes it is all three at once.

If you ever want to understand the Pacific Northwest, descend into Hood Canal when the water turns green and the current softens. Look for the places where color gathers on the stone. Where tiny tentacles reach and sway. Where something motionless begins to feel like it is breathing with the sea.

Anemones are easy to overlook, but once you notice them, they pull you in. They are the quiet machinery of the ecosystem, visible only when you slow down enough to see them. They filter water, provide habitat, feed predators, and shape entire stretches of shore with time and patience.

On one late-winter dive, I found a single giant green anemone perched on a rock, its tentacles half-closed against the surge. I hovered there, just watching it. A whole world moving around a creature that stayed fixed in place. I raised my camera, took the shot, and realized something simple.

Not every marvel in the Salish Sea chases you or darts across your light, trying to be seen. Some simply wait to be noticed. And once you do, you begin to see the seafloor differently. You understand how much depends on what stays still.

THOM ROBBINS BIO

I spend as much time underwater as life allows, teaching diving and photography, chasing the perfect shot, and writing both nonfiction and fiction inspired by these waters. You can explore more of my work at www.thomrobbins.com.

When a Tree Falls in the Forest

Learn how to stay safe around trees while hiking or camping. Understand wind, weather, and tree hazards, recognize warning signs, and plan ahead for forest safety.

Trees are ever-present above us when visiting or camping in the forest. Yet, too often, we are unaware of the risks associated with trees. Trees and branches can fall at any time and at any location for lots of reasons, including weather, age, fire, damage and disease.

Avoid spending time in the forest on very windy days. If you are visiting a park on a windy day and hear trees and branches falling, leave the forest or go to an open area. Be aware of recent weather. Be particularly careful imme-diately following strong winds, heavy snowfall, or ice storm. Wind can break branches or uproot trees. Heavy snow and ice can weaken and break trees. Storm damage can take days to reveal itself and days or weeks to clean up. Avoid stopping to spend time under dead and unhealthy trees. Trees with missing needles or leaves, peeling bark, or missing limbs may be dead. Dead limbs and trees can fall without warning. Trees can have other defects that can cause them to fall such as internal rot, broken tops, weak branch connections, open cavities, or insect and disease activity. Not all defects are visible.

Be prepared and share your plans. Trees can fall and block roads or trails. Bring emergency supplies in case your adventure lasts longer than you planned.

Winter Getaways & Holiday Traditions in Mason County

Winter in Mason County is slower — and that’s the point. Cozy stays, quiet forests, Hood Canal views, and holiday traditions like Festival of the Firs make it an easy winter escape. From waterfront cabins to warm resort stays, this is a season made for slowing down.

Winter in Mason County has a different pace. The crowds thin out, the forests go quiet, and the Hood Canal takes on a calm, moody feel that makes it easy to slow down. It’s the season for cozy stays, cold-air walks, and warm places to gather afterward.

Tucked along the forested shores of the Hood Canal on the Olympic Peninsula, Mason County becomes a low-key winter retreat. Whether you’re visiting for holiday events or just looking for a quiet escape, the area offers a mix of small-town charm, outdoor access, and places that feel right for the season.

Where to Stay This Winter

Shelton is a natural home base during the holidays. Festival of the Firs events, downtown shopping, dining, and community activities all center here, and everything is close. Lodging ranges from simple, budget-friendly motels to full-service resort stays.

The Shelton Inn remains a longtime community staple, especially convenient if most of your plans are in town. The Super 8 offers a straightforward stay uptown. For a more amenity-filled experience, Little Creek Casino Resort provides spacious rooms, dining, entertainment, and a warm place to unwind after a cold winter day.

If you’re drawn to the water, Hood Canal communities like Union, Hoodsport, and Lilliwaup are especially appealing in winter. Foggy mornings, still water, and quiet docks set the tone. Alderbrook Resort & Spa in Union offers lodge-style rooms and renovated cottages with canal views that feel especially fitting this time of year. It’s an easy choice for anyone looking for a comfortable winter escape with on-site dining and spa options.

In Hoodsport, The Glen offers a great balance between outdoor access and comfort. Close to winter hikes like Rocky Brook Falls, it’s the kind of place where you can spend the day outside and settle in by a fire at night. The Glen is also offering a winter special: stay two nights and get the third free.

For a slower, more residential feel, Allyn and Belfair offer easy access to waterfront parks, trails like the Theler Wetlands, and a relaxed pace. Located in the northeastern part of Mason County near Kitsap County and Bremerton, they’re well suited for travelers who want calm surroundings without being far from events or outdoor options. In Mason County, nothing is very far away, especially when it comes to hikes and views.

Winter Traditions & Holiday Events

Mason County isn’t just a place to stay — it’s a place that leans into the season. Festival of the Firs brings holiday traditions to life with parades, lights, crafts, and community gatherings rooted in the region’s timber heritage. Events like Christmastown at Camp Grisdale add caroling, wreath making, visits with Santa, and family-friendly activities that feel familiar and welcoming.

These winter events pair well with simple days: a morning walk along the canal, an afternoon hike through damp forest trails, and an evening spent downtown or back at your lodging warming up.

A Winter That Sticks With You

Winter here is about small moments — waking up to mist on the water, breathing in cold air, and moving through towns that feel connected and unhurried. Whether you stay close to Shelton’s holiday energy or tuck yourself away along the canal or in the woods, Mason County offers a winter experience that’s quiet, comfortable, and easy to settle into.

And if you find yourself planning a return visit, the same cabins, cottages, and resorts that feel cozy in winter become gateways to kayaking, forest walks, and long summer days by the water. Mason County has a way of fitting every season — winter just happens to show it at its calmest.

America 250 Mason County Celebrates A Year Of Community

America 250 Mason County has spent 2025 honoring the signing of the Declaration of Independence and building momentum toward July 4, 2026—America’s 250th birthday. Thanks to local partners, volunteers, and community members, history has come to life through events, presentations, and celebrations across Mason County. More activities and opportunities to get involved are ahead as the countdown to 250 continues.

Guided by historical societies at the federal, state, and local levels, America 250 Mason County has spent 2025 honoring the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. As we approach July 4, 2026—the 250th anniversary our community has enjoyed a variety of events designed to celebrate our shared heritage, with even more activities planned for the coming year.

America 250 Mason County extends its heartfelt appreciation to the many organizations, partners, and volunteers who have supported our mission throughout 2025. Their generosity and enthusiasm have brought history to life across the region.

We offer special thanks to: The City of Shelton, the Wilde Irish Pub, and North Mason Community Voice for hosting the Two Lights for Tomorrow presentations. Forest Festival and Loop Field organizers for welcoming our participation in both the Forest Festival Parade and the Loop Field festivities. Oyster Fest organizers for providing space to commemorate the 250th anniversaries of the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and the U.S. Post Office— along with a heartfelt thank-you to all who have served in the military and to those who have helped deliver the mail. Festival of the Firs organizers for creating a joyful setting filled with Christmas and winter cheer. We are also grateful to the hundreds of visitors who added their names to our replica copy of the Declaration of Independence. Your signatures symbolize a living connection to the spirit of 1776, and we look forward to offering even more opportunities to sign in 2026.

Next year promises to be an exciting continuation of our journey toward America’s 250th birthday, with new partnerships and even more engaging community events on the horizon.

For those who would like to take part in creating these meaningful experiences, we welcome your involvement. Please contact Sandy at 360-229-2882 or Will Harris at 702-250-4301 to learn how you can join the celebration.

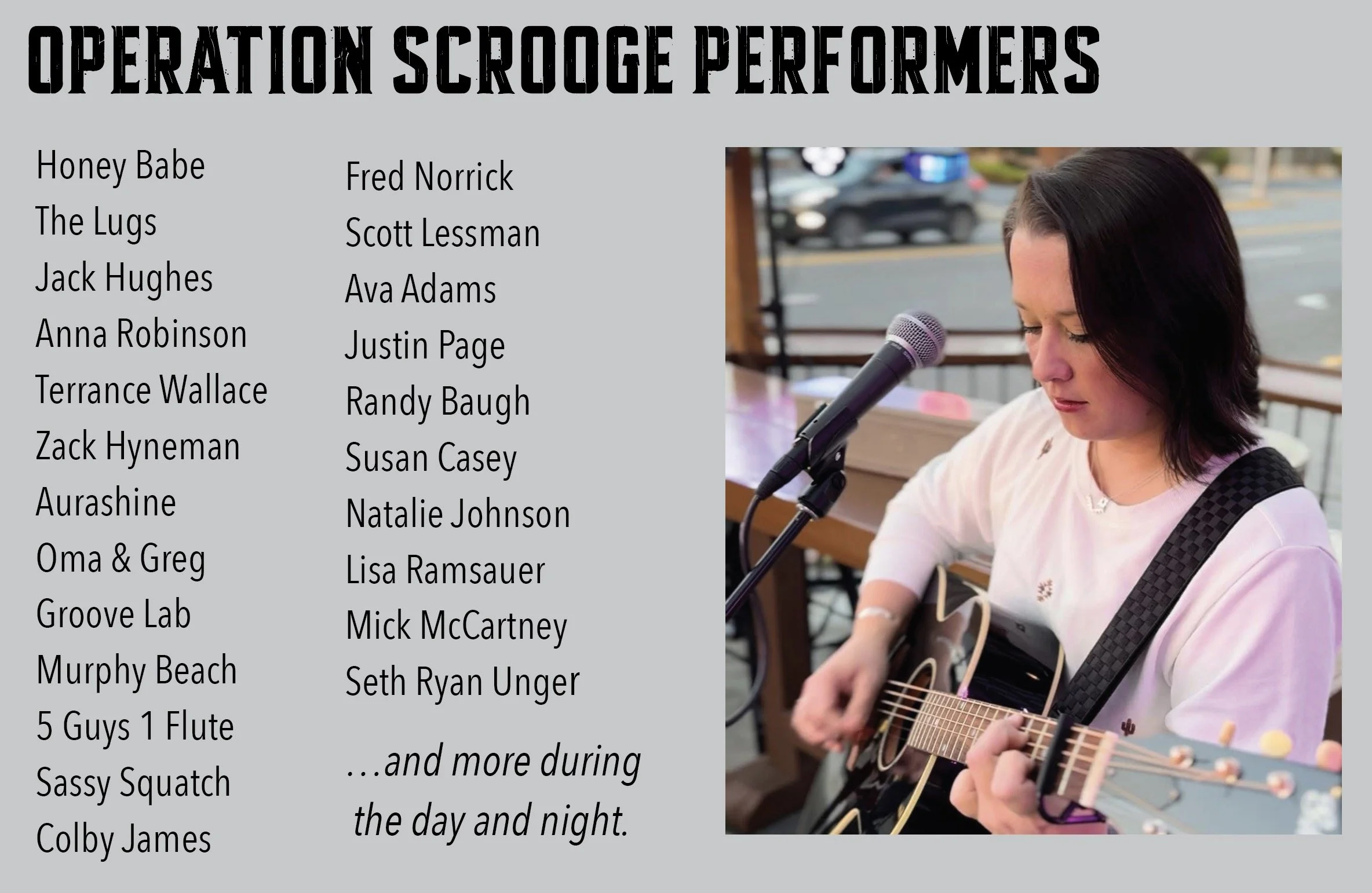

Operation Scrooge

This December, the historic Robin Hood Village Resort on Hood Canal will transform into a full-scale, multi-room production studio for one extraordinary purpose: bringing the magic of Christmas to local families in need. From noon on December 13 to noon on December 14, Operation Scrooge will host a 24-hour live-streamed music telethon, featuring 24 artists over 24 hours—a marathon of generosity, artistry, and community spirit.

This December, the historic Robin Hood Village Resort on Hood Canal will transform into a full-scale, multi-room production studio for one extraordinary purpose: bringing the magic of Christmas to local families in need. From noon on December 13 to noon on December 14, Operation Scrooge will host a 24-hour live-streamed music telethon, featuring 24 artists over 24 hours—a marathon of generosity, artistry, and community spirit.

Operation Scrooge began decades ago in a small Western New York town, where a compassionate teacher—Mr. Schuster—rallied his eighth-grade students to raise funds for families lacking the means to celebrate the holidays. One of those students remembers crossing snowy railroad tracks on Michigan Street to deliver gifts to neighborhood children he knew well. That experience stayed with him for life.Now living in Union, Washington, he and his wife have brought the tradition westward.

“When I discovered how much need exists within my own community, I knew it was time,” he shared. “Union is one of the greatest places on Earth—full of heart, full of music—and this is our chance to give back.”

In partnership with the beloved Hoodstock Music and Arts Festival, Operation Scrooge has secured the Robin Hood Village Resort for a full 24 hours of continuous entertainment. Local businesses, including Mosquito Fleet Winery, have joined in the effort—sponsoring a special “Paint and Sip” experience happening on-site during the telethon.

The live stream kicks off at noon on the 13th with fan favorites Honey Babe, and won’t sign off until Seth Ryan Unger wraps things up at noon on the 14th. Audiences can expect an eclectic lineup of musicians each donating their time and talent. Every hour brings a new act. Every act brings Operation Scrooge one step closer to helping local families experience the joy of the holiday season.

Honey Babe | Hoodstock 2025 photo

A Community Comes Together

Operation Scrooge is partnering with the Hood Canal School District to identify families facing the steepest challenges this year. More than 50 families are already hoping for assistance, and the goal is to help as many as possible. Every dollar raised stays right here on the canal, supporting local households with gifts, essentials, and a much-needed reminder that their community cares. The entire event will be streamed live on multiple platforms, welcoming viewers from around the world to enjoy the performances and contribute if they can.

The spirit of Mr. Schuster’s original project—neighbors helping neighbors—continues to burn bright, now illuminating the shores of Hood Canal .“Help us keep the tradition alive,” says Chris, “Let’s bring a smile, and the magic of Christmas, to those who need it most.”

Whether you donate, tune in, share the event, or simply help spread the word, your involvement makes a meaningful difference. Watch the livestream here:

Facebook: Operation Scrooge

youtube.com/ChrisEakesMusic

twitch.com/ChrisEakes

Hoodsport’s Yule Fest Celebration | DEC 13

Celebrate Hoodsport with caroling and events throughout town, December 13. Street booths begin to open around 3 PM and caroling begins at 530 PM.

Celebrate with Caroling, Crafts & Community! The Hoodsport business community is pleased to announce the third annual holiday downtown Hoodsport celebration – Yule Tide!

Families can enjoy activities, food and local shopping and festivities during the afternoon through early evening at businesses throughout town.

Look forward to caroling starting at the Christmas tree at Hoodsport Marina as at 5:30 PM. The carolers will stroll through Hoodsport with stops at businesses along the way.

Potlatch Brewery will once again host Santa Paws where you can get pictures with your pets and Santa Claus. They will also serve drinks and food available for purchase. The Hardware Distillery will be joined by The Tides on 101 Restaurant, serving up chowder for purchase. Canalside will be joined again by the Hood Canal Kiwanis Club for craft activity and pictures with Santa and Mrs. Claus and serving hot chocolate and cider. Local artists and craftspeople will be on site to provide guests with last minute gifts (starting around 1PM) and Canalside will be open late.

The Model T and other local businesses will join on the event with activities and warm treats for the traveling carolers as they traverse the route through town!

The caroling ends at Fjord Oyster Bank where there will be fire pits and free cocoa & marshmallow roasting. The Fjord will also host activities for families.

Parking is available along the street as well as at YSS Dive and Canalside parking lots, the Hoodsport Fish Hatchery and the Fjord Oyster Bank Restaurant.

For additional details on this events and others in the area including musical events and workshops, visit festivalofthefirs.com

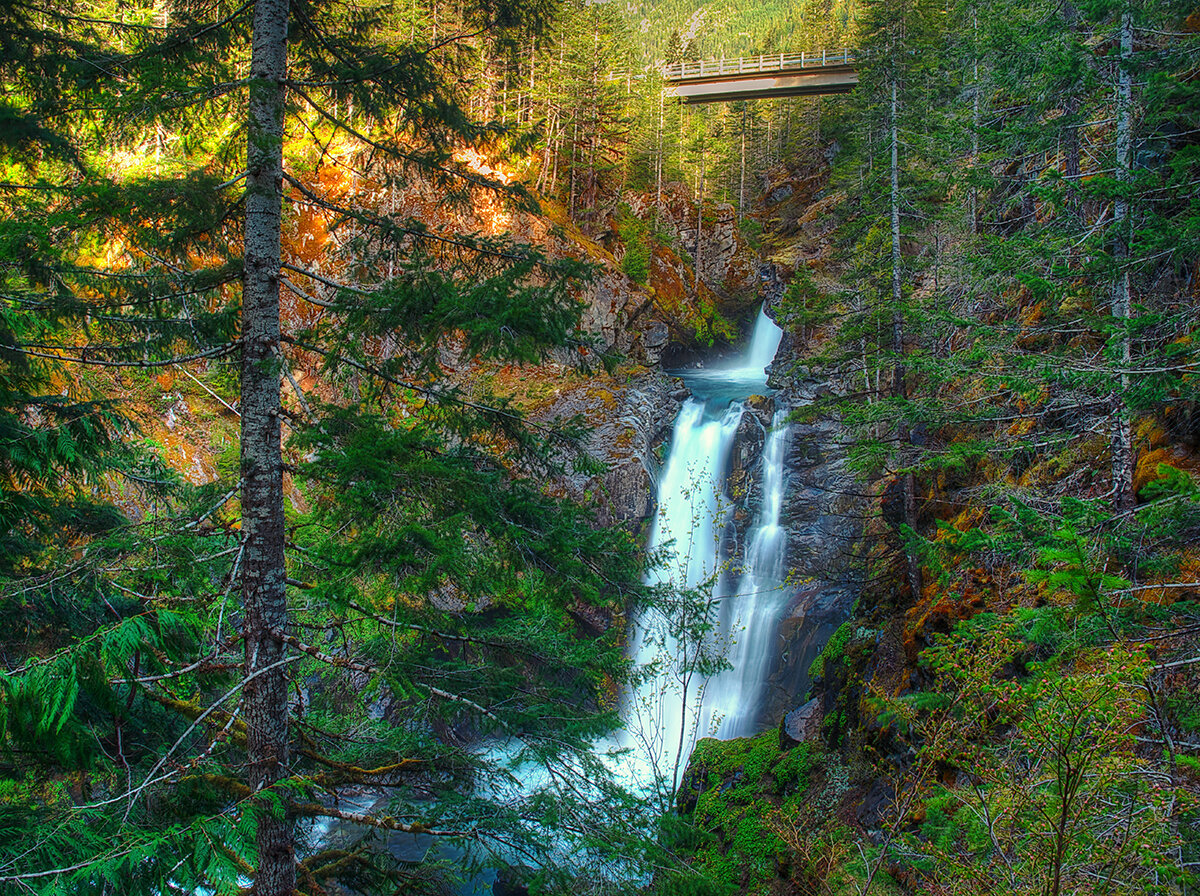

A Guide to 25 Waterfalls from Canal to Coast and points between

Receiving hundreds of inches of rain annually, the Hoh, Quinault and Queets Rainforests are located on the coastal foothills of the Olympics, receiving 21+’ of snow and rain at its peaks! It’s no wonder there is a myriad of spectacular waterfalls lacing the area. Explore this sampling curated by celebrated guidebook author and avid hiker, Craig Romano. Some are small, secret, and unique, others are popular but magnificent. All are worth the journey!

When Craig Romano agreed to share with us a few of his favorite waterfalls in the Pacific Coastal region of Washington, we were frankly thrilled. If you’re looking for straight details on Northwest hikes and wilderness destinations — and fun facts - Craig is the guy to call.

Craig has written more than 20 hiking guidebooks including Day Hiking Olympic Peninsula 2nd Edition which includes details for popular and little known hikes across the Peninsula. An avid hiker, runner, paddler, and cyclist, Craig is currently working on Urban Trails Vancouver USA (2020); Backpacking Washington 2nd Edition (2021); and Day Hiking Central Cascades 2nd Edition (2022). He is also a featured columnist for the Fjord and Explore Hood Canal.

Enchanted Valley | Craig Romano photo

Why we are so keen about our falls?

As storms from the Pacific Ocean move across the peninsula, they crash into the Olympics and are forced to release moisture in the impact. Consequentially, the clouds release massive amounts of moisture (up to 170 inches annually) in the coastal side of the range – creating the “rain shadow effect.”

The massive rainfall has given life blood to the hanging mosses of the perpetually wet Northwest rainforests – Hoh and Quinault. On top the Olympic Mountains this moisture lands as snow frosting the peaks with as much as 35 feet each year.

Each spring the snow melts and creates icy run-off. Mix in a little more rainfall and the result is a spectacular waterfalls ring envelops the base of Olympic range.

Pacific coastal waterfalls are gorgeous year round but tend to be most spectacular in early spring or during the autumn rainy season.

Let’s go Chasing Waterfalls

1. Tumwater Falls

Olympia Metro | Located minutes from Olympia, Tumwater Falls is an iconic landmark near the state capital. These thundering multi-tiered showy falls along the Deschutes River are located within a 15-acre park created on land donated by the Olympia Brewing Company. Meander along manicured paths and saunter over foot bridges and under historic road bridges taking in a little history along with the sensational scenery.

At the base of the upper falls admire a replica of the famous bridge that once appeared on the labels of Olympia beer spanning the river above the lower falls. Walk trails along the gorge between the falls and admire deep pools, eddies and jumbled boulders. Take time to read the informative panels on Tumwater—Washington’s oldest permanent non-Native settlement on Puget Sound. Let’s Go!

2. Kennedy Creek Falls

Kamilche, South of Shelton | From its origin at Summit Lake in the Black Hills, Kennedy Creek flows just shy of 10 miles to Oyster Bay tumbling over a two-tiered waterfall along the way. Reaching these pretty falls involves a half day hike on a closed-to-vehicles logging road through patches of cuts and mature standing timber. Start walking across a recent cut. In about a mile reach a grove of mature timber and the Kennedy Creek Salmon Trail which opens in the fall for salmon viewing and field trips. Keep walking on the main road avoiding diverting roads. The route leaves state land for private timberland and rolls along. Take in decent views of the surrounding foothills. At 2.8 miles (just before crossing a creek) follow an obvious but unmarked trail to the right. This path can be muddy and slick during periods of heavy rainfall. The trail descends to a grove of big cedars, firs and yews—and the falls. Here Kennedy Creek tumbles over an ancient basalt flow. The upper falls are small but quite pretty. The lower falls are difficult to see as they tumble into a narrow chasm of columnar basalt. Let’s Go!

3. Vincent Creek Falls

South Hood Canal, Skokomish Valley | While Vincent Creek Falls are quite stunning crashing 250 feet into the South Fork Skokomish River in a deep narrow canyon; the High Steel Bridge which allows for their viewing is even more spectacular. The 685-foot long bridge spans 375 feet above the canyon. Walk across the bridge but use caution along its north side where the guardrail is only 3 feet tall. The arched truss steel bridge was built in 1929 originally for a logging railroad. In 1950 it was converted for road use. It is the 14th highest bridge in the country. Your heart is sure to pound as you walk upon its airy span. Eventually Vincent Creek Falls comes into view. Through a series of falls, Vincent Creek drops 250 feet down a canyon wall into the roaring South Fork Skokomish River. Walk all the way across the bridge if you plan on capturing the falls in their entirety in a photo. Let’s Go!

Big Creek | Craig Romano Photo

4. Big Creek Cascades

Lake Cushman Area, Hood Canal | Amble on a circuitous route in the Big Creek drainage within the shadows of Mount Ellinor; and delight in a series of small tumbling cascades. This wonderful loop utilizes old logging roads, new trails and a series of beautifully built bridges. It was constructed by an all-volunteer crew that continues to improve and maintain this excellent family and dog-friendly loop. Starting from the Big Creek Campground, follow the Upper Big Creek Loop Trail to Big Creek and the first of several sturdy bridges along the way. After a short climb you’ll reach the Creek Confluence Trail which drops to the confluence of the tumbling Big and North Branch Creeks. The main loop continues to cross North Branch Creek on a good bridge. Just beyond it crosses Big Creek on a new bridge above a gorgeous cascade. The loop then descends skirting big boulders and passing good views of roaring Big Creek. It crosses a couple more cascading creeks before traversing attractive forest and returning to the campground. Let’s Go!

5. Staircase Rapids

Lake Cushman Area, Hood Canal — Currently Closed until mid-September

This loop involves a section of an historic route across the Olympic Mountains to a suspension bridge spanning the North Fork Skokomish River near a series of thundering rapids. Cross the North Fork Skokomish on a solid bridge and follow a trail that was once part of the original O’Neil Mule Trail. In 1890 Lieutenant Joseph O’Neil accompanied by a group of scientists led an Army expedition across the Olympic Peninsula. Among his party’s many findings was a realization that this wild area deserved to be protected as a national park. March up alongside the roiling river, passing big boulders and a series of roaring rapids. The rapids’ name come from a cedar staircase O’Neil built over a rocky bluff to get past them. Follow the bellowing river from one mesmerizing spot to another before reaching a sturdy suspension bridge spanning the wild waterway. Cross the river and complete this delightful loop by now heading downriver following the North Fork Skokomish River Trail back to the Ranger Station. Let’s Go!

Hamma Hamma | George Stenberg photo

6. Hamma Hamma Falls

Hamma Hamma River Valley, Hood Canal | Talk about a bridge over troubled waters. From the Mildred Lakes Trailhead walk across the high concrete bridge at the road’s end. You no doubt heard the roar of the falls when you drove across it. Now peer over the bridge and witness the cataracts responsible for the racket.

Directly below, the Hamma Hamma River careens through a tight rocky chasm. These impressive falls are two-tiered crashing more than 80 vertical feet. The road spans directly above the upper and smaller of the falls. The overhead view is pretty decent, but the lower and larger falls are more difficult to fully see. A very rudimentary path leads along cliff edges for better viewing, but it’s slick, exposed and treacherous.It’s best to experience the falls from the safety of the bridge. During periods of high water flow you’ll get the added bonus of feeling the falls too thanks to a rising mist. On the drive back look for a couple of pull-offs providing views of secondary falls along the Hamma Hamma, Let’s Go!

7. Murhut Falls

Duckabush River Valley, Hood Canal | Hidden in a lush narrow ravine and once accessed by a treacherous path, Murhut Falls were long unknown to many in the outside world. But now a well-built trail allows hikers of all ages and abilities to admire this beautiful 130-foot two-tiered waterfall. The trail starts by following an old well-graded logging road. It was past logging in this area that led to the discovery of these falls. The old road ends after a short climb of about 250 feet to a low ridge. The trail then continues on a good single track slightly descending into a damp, dark, cedar-lined ravine. As you work your way toward the falls, its roar will signal you’re getting closer. Reach the trail’s end and behold the impressive falls crashing before you. The upper falls drops more than 100 feet while the lower one crashes about 30 feet. Blossoming Pacific rhododendrons lining the trail in May and June make the hike even more delightful. Let’s Go!

Rocky Brook Falls

8. Rocky Brook Falls

Dosewallips River Valley, Hood Canal | One of the tallest waterfalls on the Peninsula, Rocky Brook Falls is also among the prettiest. Follow the trail past a small hydroelectric generating building and come to the base of the stunning towering falls fanning over ledges into a large splash pool surrounded by boulders. This classic horsetail waterfall crashes more than 200 feet from a small hanging valley above. While a penstock diverts water from the brook for electricity production, the flow over the falls is almost always pretty strong. Like all waterfalls, these too are especially impressive during periods of heavy rainfall. On warm summer days the falls become a popular destination for folks seeking some heat relief. And while many waterways east of the Mississippi River are called brooks, creek is the preferred name in the west. There are only a few waterways on the Peninsula called brooks, and they were more than likely named by someone who hailed from back east. Let’s Go!

9. Dosewallips Falls

Dosewallips River Valley, Hood Canal | This spectacular waterfall used to be easily reached by vehicle. But the upper Dosewallips Road has been closed to vehicles since 2002 after winter storms created a huge washout that has yet to be repaired. Now to reach this waterfall you must hike or mountain bike the closed road. Walk past the road barrier and immediately come to the washout and a bypass trail. Steeply climb on the riverbank above the slide. Then descend back to the road and walk along the churning river. The road then pulls away from the river, passes a campground and climbs. The river now far below in a canyon is out of sight, but not out of sound. Pass beneath ledges and cross cascading Bull Elk Creek on a bridge. At 3.9 miles in a recent burn zone enter Olympic National Park. Cross tumbling Constance Creek on a bridge and continue climbing passing a big overhanging boulder. Then descend and skirt beneath a big ledge coming to the base of dramatic 100-foot plus Dosewallips Falls. Admire the raging cascade’s hydrological force—it’s mesmerizing. Let’s Go!

10. Fallsview Falls

Big Quilcene River Valley | As far as cascades go, Fallsview Falls lacks the “Wow factor.” However the canyon these falls tumble into is pretty impressive. And if you plan your visit for late spring, blossoming rhododendrons line the trail and frame the view with brilliant pinks and purples. The trail to the falls is short, easy and ADA accessible. Follow the 0.2 mile loop to a fenced promontory above a tight canyon embracing the Big Quilcene River. Gaze straight down to the roiling river. Then cast your glance directly across the canyon to an unnamed creek cascading 100 feet into it. By late summer it just trickles—but during the rainy season the falls put on a little show. If you want to stretch your legs some more afterward, you can follow a trail into the little canyon and hike along the frothing river. Let’s Go!

And 15 more…

For a day trip, weekend, or a month-long adventure – the Olympic Peninsula is a fantastic place to get away and enjoy nature – and waterfalls! It’s not just 1000’s of waterfalls, there are countless lakes, rivers, streams and trails to suit every ability level. Embraced by the Pacific Ocean on the west, the Strait of Juan de Fuca on the north, and the Hood Canal on the east, it is famed for being home to Olympic National Park, more than 600 miles of hiking trails and 73 miles of pristine ocean wilderness beaches.

The Olympic Peninsula hosts activities for families and outdoor enthusiasts alike, attracting visitors from near and far. Start planning your next adventure!

Click here for a complete list of all 25 waterfalls on the Olympic Peninsula curated by Craig!

Holiday Magic in Shelton | DEC 5-6

Despite the rain and sleet, the holiday spirit is alive and well this week in Shelton as volunteers deck the downtown streets and prepare for the big Christmastown seasonal kick-off, Holiday Magic, December 5-6.

Christmatown is alive with holiday magic

If you don’t like Hallmark movies, stay away from Shelton, next weekend as the holiday spirit is alive and well here this week as volunteers deck the downtown streets and prepare for the big seasonal kick-off, Holiday Magic, December 6-7.

The festivities start Friday with the opening of the 2025 Guinness Ttribute Christmastown Maze and Camp Grisdale on Cota Street next to the Shelton Civic Center. For the 6th year in a row, the maze has welcomed families to enjoy a festive FREE activity with the support of local non-profits that host cocoa and marshmallow roasting pits each evening.

Friday, DEC 5 starting at 4 PM, head over to the maze or some fun FREE activities at KMAS Radio and the Morning Show Host, Jeff Slakey, host the a Community Christmas Party with crafting, music, wreath workshops, food, and a selection of local vendors.

Interested in building a cookie palace? Be sure to get your gingerbread entries into the Shelton Mason County Chamber office by 5PM, Friday!

At 6 PM Friday the crowds will be gathering in Post Office Park for the return of the Shelton tree lighting hosted by the Kristmas Town Kiwanis and Shelton Downtown Merchants. Enjoy choirs of school children singing carols and free hot chocolate and cookies sponsored by 2nd Street Design.

The street party continues on Railroad Avenue with fire pits in the street to roast marshmallows and kiddie train rides as well as evening shopping (until 8) at downtown merchants. Be sure to pick up a Shop Local First rewards card and uses it at participating merchants to win great prizes.

Santa Claus Parade Saturday

At 5 PM Saturday Kristmas Town Kiwanis and the Shelton Downtown Merchants clear the streets for the Christmas Parade. Peninsula Credit Union will be hosting free hot chocolate.

Another spot to tie the knot

Planning a wedding? It’s never too soon to be scoping out locations! Hood Canal’s Mike’s Beach Resort is embracing a new chapter, with the opening of the brand-new Salish Hall, a stunning indoor event space on the waterfront, the resort now offers couples more opportunities to celebrate a local destination wedding surrounded by breathtaking views and timeless beauty.

For generations, Mike’s Beach Resort has been a beloved Pacific Northwest getaway — a place where families return year after year to relax, reconnect, and take in the stunning natural beauty of the Hood Canal. Nestled between the majestic Olympic Mountains and the calm, shimmering waters of the canal, this historic resort offers an authentic slice of coastal Washington charm. From its classic waterfront cabins to cozy family rooms and glamping tents, Mike’s has always been about creating lasting memories in the heart of nature.

Now, as the resort continues its legacy, the classic lodging staple is embracing a new chapter — becoming one of the region’s waterside wedding and event destinations. With the opening of the brand-new Salish Hall, a stunning indoor event space on the waterfront, the resort now offers couples the opportunity to celebrate their love surrounded by breathtaking views and timeless beauty.

Introducing Pine and Tide Events

Welcome to Pine and Tide Events, where the natural beauty of the Pacific Northwest meets thoughtful design. Operating at both Mike’s Beach Resort and Iliana’s Glamping Village, Pine and Tide provides a range of unique venues and accommodations perfect for all inclusive weekend wedding celebrations - including a range of outdoor activities in the woods and on the water.. Whether it’s an elegant waterfront ceremony at Mike’s or a woodland vow exchange at Iliana’s Glamping Village, the updated venue offers a flexible canvas for your dream wedding. Celebrate surrounded by the scent of cedar and salt air, and let nature be your backdrop.

The Venues

Mike’s Beach Resort

Up to 68 overnight guests

Waterfront ceremony and reception space

Brand-new Salish Hall for indoor celebrations

Bridal prep suite and groom’s flex room

Pet-friendly accommodations

Waterfront cabins, family rooms, and cozy motel rooms

Iliana’s Glamping Village

Up to 28 overnight guests

Woodland ceremony space beside a tranquil stream

Lawn reception area and Wildwood Wedding Bar

Rustic-luxury glamping tents with modern comforts

Together, these venues offer the perfect blend of comfort, adventure, and natural beauty, making them ideal for couples seeking a relaxed, immersive wedding experience that extends beyond a single day.

We especially love that they have a wedding venue supply “closet!” WOW — what a fun Pinterest moment!

Beyond the celebrations, Mike’s invites guests to experience the simple joys of coastal exploring — from gathering around open-air fire pits and BBQs on the waterfront, to harvesting your own oysters and clams at the resort’s private U-Pick shellfish beach. And with Olympic National Park and a host of hikes are just a short drive away, adventure is always within reach. Slow down, reconnect, and celebrate life’s most meaningful occasions surrounded by the natural splendor of the Pacific Northwest.

Following fall around the Fjord

Autumn is one of the most stunning times to explore Mason County. With crisp air, golden leaves, and peaceful waterways, every turn offers a postcard-worthy view. Whether you’re a local looking for a weekend adventure or a visitor planning a scenic day trip, Mason County’s natural beauty truly shines this time of year.

Jeff Slakey | EHC contributor

This past week, I spent the day traveling around Mason County, capturing some of the incredible fall colors, and it couldn’t have been a better day for it.

I started at a foggy Lake Isabella State Park before heading into Shelton to see the waterfall at the Teresa Johnson Trail. Along the way a great spot to pause and admire the view at Outlook Park just south of Shelton. Along with fantastic views of the Olympics and the fall colors over the terminus of Hammersly Inlet, you’ll be able to check out the 32’ oysterman mural posted for October’s OysterFest event. Soon he’ll be changed out for the iconic Santa Claus reproduction from 1965 — heralding yet another change of the season. From there I headed down through the impressive leafy tunnel descending into Shelton. A quick pitstop on Cota Street to grab a coffee at Marmos, then a right, following Highway 3 past the Oakland Bay Marina, where a few seals were playing near the docks. After that, I cranked up KMAS and hit the road again with stops at Oakland Bay Preserve to check out the salmon runs.

Back in the car I headed back to Hwy 101 and north to Potlatch State Park where you get a great vantage of the colors on the far banks of the Canal. This is a great spot to pause. Trees laden with apples and tons of wildlife. I spotted a heron patiently hunting for lunch, perched on a buoy.

As the afternoon progressed and the sun started shining, I left Potlatch to see what the salmon were doing near the Hoodsport Hatchery. They were making their way up Finch Creek, dodging fishermen casting lines nearby. Before my camera batteries died, I was heading back south toward Shelton. I took the Skokomish Valley Road and headed up to the High Steel Bridge. By then, the fog had lifted, and the views of the canyon were as clear and bright as the fall leaves.

You don’t have to hit all those spots in one day like I did. In fact, when the weather’s nice (and there are still plenty of nice days left!), stop at just one or two to really soak in the beauty of Mason County this time of year. Or maybe keep following the curves of the Canal and make your destination Hama Hama Oysters at Lilliwaup. Every bend is worth whipping out the good lens.

Happy exploring.

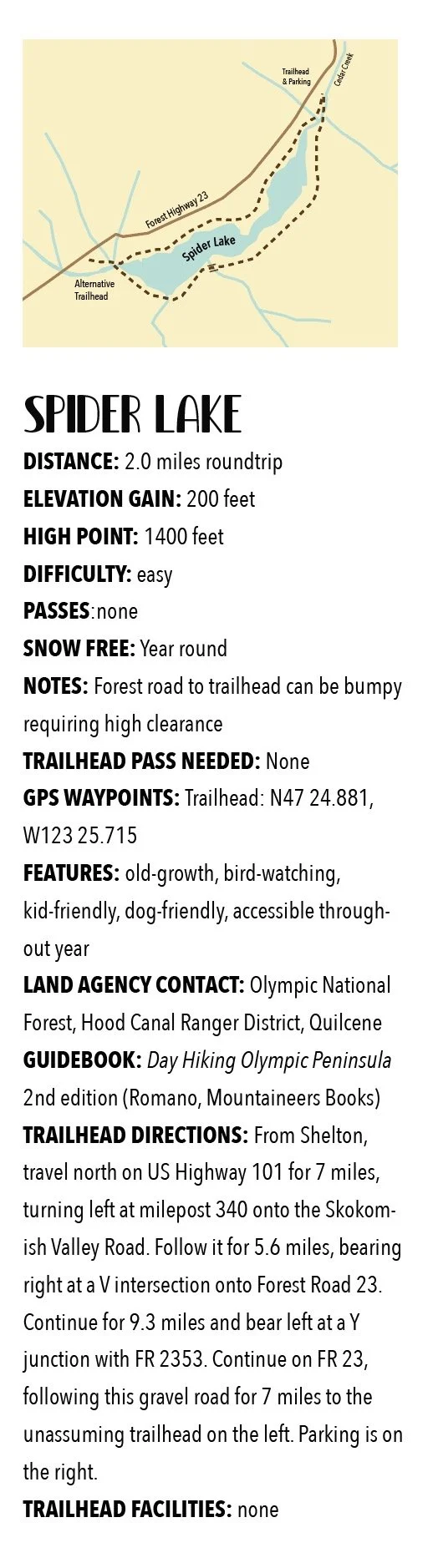

Spider Lake: Perfect year round hiking destination

With a name that may instill a chill if you’re prone to arachnophobia, fear not a visit to Spider Lake. Children will love hiking along its shores looking for birds, fish, amphibians and other critters. They’ll also appreciate the well-built bridges spanning the lake’s inlet and outlet streams. And the trail with its gentle course around the lake is ideal for hikers of all ages and abilities.

With a name that may instill a chill if you’re prone to arachnophobia, fear not a visit to Spider Lake. The small lake on the South Fork Skokomish River—Satsop River divide is actually an inviting place. Surrounded by towering ancient conifers and fed by cascading creeks, Spider Lake is quite tranquil. Children will love hiking along its shores looking for birds, fish, amphibians and other critters. They’ll also appreciate the well-built bridges spanning the lake’s inlet and outlet streams. And the trail with its gentle course around the lake is ideal for hikers of all ages and abilities.

Hit the Trail

Hikers of a certain age may start humming the Jim Stafford classic Spiders and Snakes upon beginning their jaunt to this lake. And if you’re in agreement to the chorus of “I don’t like spiders and snakes…” take solace. There are only three species of snakes that call the Olympic Peninsula home, and none of them are venomous. However there are more than 900 species of spiders that reside on the peninsula! Yet, the majority of them you’ll never encounter. And the common ones, crab spiders, jumping spiders, and orbweavers are nothing to be afraid of. You’re more likely to run into their webs (especially if you’re the first one on the trail that day) than into them. Voracious eaters of insects, spiders help keep the population of those hiking nuisances down.

So is there an abundance of spiders at Spider Lake? No—no more than pretty much anywhere else in the Olympics. So what’s with the name? No one’s quite sure, as any record to how this lake got its name can’t be easily found. Spider Meadow in the Cascades Mountains is named after a mine, so that’s a possibility. Spyder Lake in Quebec and Spider Lake in Minnesota are named for their shapes resembling the arachnid. Is this lake shaped like a spider? No, it’s shaped more like a flatworm. Perhaps an early explorer simply named the lake after the arachnid because he had a spider encounter there—who knows?

In any case Spider Lake isn’t grand in any sense, this hike’s main draw is its trees. The lake is surrounded by gorgeous ancient forest—a tiny fragment of the grand forest that once shrouded the hills and ridges along this entire divide. The trail too is a fragment—once a much longer route connecting the South Fork Skokomish River Valley to the Satsop River Valley. Decades of intensive logging in this corner of Olympic National Forest not only obliterated the area’s primeval forest but also much of its extensive trail system.

With the cut now a fraction of what it once was and with trail usage at record numbers, it would be a great time to bring folks together to start rebuilding trails in the southern Olympic flank.

In the mid-1990s, trail builders resurrected a portion of the old trail that once traveled up the Cedar Creek valley and constructed adjoining new tread to build a two-mile loop around little Spider Lake. Trail-building aficionados will probably find the loop’s three large bridges noteworthy for their durability and aesthetics. Kids will love crossing them—probably doing a few repeats on the spans.

This trail is a joy to hike anytime of the year, but it glows pearly white in early summer when blossoming dwarf dogwood and queen’s cup blanket the forest floor. A few shrubs and sedges will add some golden touches in autumn. From the trail’s unassuming trailhead (there’s another unassuming trailhead to the south) immediately enter cool old-growth forest and come to a junction. Turn right (although either direction will work), crossing the outlet stream and soon reaching Spider’s western shoreline. Now saunter past towering trees, good fishing spots, and excellent viewpoints of the placid lake. Look for avian and amphibious residents. Cast your glances upward at the surrounding ridges. These intensively logged hillsides offer quite a contrast to the virgin groves cradling the lake.

After about a mile, cross a small creek and reach a junction. The trail heading right steeply climbs a short distance to an alternative trailhead. Continue left climbing a little above the green waters of the lake while being shaded by ancient behemoths. Now continue along the eastern shoreline climbing a bit more to traverse a steep slope.

After crossing a high log bridge, the trail begins its descent back to lake level. It then crosses an inlet stream in a marshy area before returning to the junction where you started your trip around the lake.

The hike is short, but the surroundings beckon you to slow down and enjoy the natural beauty of this small lake and its big trees. Perhaps you’ll be fortunate to see some wildlife along the way—and more than likely you probably won’t recall if you encountered a spider or two!

contributor

Craig Romano is an award-winning guidebook author whose deep connection to Washington trails, dedication to accuracy, and passion for conservation have made him a trusted name in the outdoor community. His contributions to Tracing the Fjord magazine bring rich, informed outdoor narratives to a readership that lives and loves the Hood Canal region. Craig's guidebooks stand out for their thorough research. He physically scouts trails, GPS-tracks routes, and includes lesser-known—and at-risk—options to offer diverse, accurate, and reliable resources for hikers. He incorporates sidebars with natural or cultural history and conservation insights in his writing. He emphasizes responsible use and stewardship of trails, challenging readers to be “good conservation and trail stewards.” Craig has written more than 25 guidebooks, including celebrated “Day Hiking” and “Urban Trails” series published by Mountaineers Books—featuring areas like the Olympic Peninsula, Vancouver BC, and beyond.

Crabby Characters: Stories from the Seafloor

Spend enough time beneath the surface of Hood Canal, and the silence starts to speak not in words, but in motion. Everything down there moves slower in the cold except the crabs. The crabs are always busy. Always urgent. I’ve watched one spend ten full minutes excavating a hole no deeper than a coin is thick, only to abandon it and scuttle off as if remembering something more important.

Thom Robbins | story and picturesSpend enough time beneath the surface of Hood Canal, and the silence starts to speak not in words, but in motion. Everything down there moves slower in the cold except the crabs. The crabs are always busy. Always urgent. I’ve watched one spend ten full minutes excavating a hole no deeper than a coin is thick, only to abandon it and scuttle off as if remembering something more important. One squared off with its own reflection in my camera dome, claws raised like a boxer waiting for the bell. And another cleaned algae off its shell, as if preparing for a first date.

They aren’t graceful like the kelp fish or hypnotic like moon jellies. They’re rough-edged little bulldozers, powered by instinct and old armor, constantly on patrol. You’ll find them under ledges, in discarded cans, perched on the pilings of a long-lost dock. Red Rock crabs, kelp crabs, decorator crabs, hermits dragging their spiral shells like tiny trailers behind them, all of them crawling, shoving, digging, sparring, eating, surviving.

To dive in Hood Canal is to enter their world, not as an observer but as a trespasser in a busy kingdom. And the deeper you go, the more you start to wonder: who’s really watching who?

There are over thirty species of crab living in the Salish Sea, and I swear I’ve startled half of them just getting my fins on. Big ones, small ones, legs like knitting needles—some so camouflaged they vanish if you look away. They're not background players down here. They're the quiet architects of the seafloor. Scavengers, cleaners, prey, and predators, they keep the submerged machine running.

Take the Dungeness crab. Everyone knows that name from a dinner menu, but out here, in the cold green quiet, you see the other side of it. These are not docile creatures. They fight like boxers in the sand, claw-to-claw. I once watched two square off over a fish head, each strike spraying up little clouds of silt. No hesitation, no mercy. The winner dragged the prize beneath a ledge and vanished. The loser waited a few beats, then started digging like it had never happened.

Red Rock crabs are the neighborhood bruisers, bad-tempered, road-shouldered, all edge. Their claws are darker than blood, twice as quick. You don’t want to get too close. They make sure you know when you’ve stayed too long.

Then there are the kelp crabs, graceful, spindly, with legs that seem to unfold forever. They cling to the long, swaying forests of bull kelp like sentries, their shells often coated in fuzz or film. I’ve seen them frozen in place for minutes, like a spider in a web—until they move. And when they do, they move fast.

But my favorite? The decorators. They’re the mad geniuses of the crab world—slow-moving and soft-shelled, but never unprepared. They tear pieces of sponge and algae from their surroundings, stitching them onto their backs like makeshift armor or fancy hats. Sometimes they vanish into the scenery. Other times, they look like moss-covered monsters crawling across the sand. I found one once with an entire anemone riding on its back, swaying as a crown.

Crabs do more than scuttle around at our feet. They oxygenate sediment, recycle waste, and form the base of countless food webs. Otters eat them. Octopuses hunt them. Even gulls have learned to flip them over like breakfast pancakes. But somehow, they endure.

Out here, beneath the weight of the water, they don’t feel small at all. They seem ancient, as if they’ve been here longer than we have. As if they know something we don’t, and maybe they do. Watch them long enough and you start to see why: crabs are built like tanks, only stranger. You don’t realize how alien they are until you’re face-to-face with one in the dark, thirty feet down. Your dive light catches the gleam off that hard, unblinking shell. They look back with stalked eyes, unmoving, weighing whether to run, fight, or decide you aren’t worth the thought.

Like spiders and shrimp, crabs are arthropods wrapped in an exoskeleton that is both armor and skeleton, with no bones inside and everything important protected on the outside. That shell, or carapace, is tough as old fiberglass, etched like a puzzle box, often scarred from past fights, and it doesn’t grow with them. When they get too big for it, they crack it open like a coffin and climb out soft and defenseless until the new shell hardens. I’ve found husks underwater that look like dead crabs until you realize they’re ghosts on the sand.

Most crabs have ten limbs, eight legs, and two claws, but don’t let the symmetry fool you. Those claws aren’t there just for show. They’re everything. I’ve watched crabs use them like tools, snapping open clam shells with surgical efficiency. I’ve seen them fight, claws locked like wrestlers on a mat, each trying to twist the other into submission. And once, on a night dive near an old piling field, I caught sight of a male crab slowly waving one claw back and forth in the beam of my flashlight, rhythmic, almost elegant, like conducting the tide. Mating display. Or maybe a warning. Hard to say. But whatever it was, it felt old. Practiced.

Even the Puget Sound king crab, the largest crab you’re likely to see in the Pacific Northwest, with a carapace that can span nearly a foot across, is unforgettable when you’re lucky enough to spot one. Its shell flashes red-orange under your dive light, edged with faint blue highlights as if brushed with frost.

Sometimes, you’ll notice asymmetry in its claws, with one noticeably larger than the other. This can happen after a molt, when a lost claw is still regrowing, or from years of favoring one claw over the other, like a boxer’s strong hand. That imbalance isn’t clumsy, it’s deliberate. Bigger doesn’t always mean better, but it does mean louder. That oversized claw speaks before the crab ever moves. It says: I’ve survived something you haven’t. I’ve fought. I’ve rebuilt.

Many of them have. Crabs here lose claws to predators, traps, and each other, but they don’t stay broken. They molt, wait, and grow it back slower, a little different, but the same. When you see that heavy claw raised like a crooked banner, it’s not just a weapon, it’s a story of survival, hard-won and costly.

Down here, everything fights to keep going—sometimes with teeth, sometimes with venom. Crabs fight with whatever they’ve got left, rebuilding one joint, one muscle fiber at a time. There’s an honesty in that brutality.

You never forget the first time you see a crab run. It’s not a graceful thing. Not smooth like a seal gliding past or a school of herring flickering in unison. It’s sharp. Sudden. Like something went off inside it. One second it’s there, perfectly still, and the next it’s gone—vanished sideways into the shadow of a rock or beneath a curtain of eelgrass.

That sideways sprint comes from design. A crab’s legs hinge on the sides, not underneath like ours. Each leg pushes like an oar, catching the bottom and shoving the body across the sand with precision. When you see it up close, there’s a rhythm to it, like a dancer on a single beat.

And when they move, they move faster than you'd think. The crabs here in Hood Canal—Red Rock, Dungeness, and the occasional Northern Kelp Crab aren’t built for land speed, but underwater? They’re spring-loaded traps. One second, they’re still, blending into sand or clinging to a piling; the next, gone. Just a blur of motion and a trail of stirred-up silt.

I’ve watched a Dungeness bolt sideways across a sandy shelf with such force it left a trench behind, vanishing beneath a ledge before I could even lift my camera. Kelp crabs don’t move quite as fast, but when they do, it’s sudden, those long, delicate legs pulling their mossy bodies up and over kelp blades like they’re trying to escape the light. Helmet crabs and graceful kelp crabs can vanish into the gloom in a blink if you come too close.

They don’t waste energy, every movement counts. When they go, it’s all at once, like something spooked in the woods, sharp and armed.

I’ve chased more than a few across the bottom camera in hand, bubbles rising just trying to land one clean shot. But more often than not, all I’m left with is a cloud of sand and a shape disappearing into shadow. That’s the game—they always win.

Not all of them run. Some freeze, legs tucked tight, trusting camouflage to outlast your curiosity. Decorator crabs are masters of this—covered in algae, sponges, and stitched-on debris, they hold so still you doubt they were ever moving at all. You notice them only when they twitch once, like something from a dream that leaves no footprints.

Others bluff. The Red Rock raises its claws in defiance, even when outmatched, daring you to come closer. And I’ve seen graceful kelp crabs pull themselves into near-vertical poses, legs extended, trying to look bigger. They don’t want to fight, but they’ll make you think.

Then there are the burrowers, smaller crabs like helmet crabs or hairy shore crabs. When spooked, they vanish downward instead of outward, kicking up sand as they wedge themselves under rocks or into old clam holes. They disappear.

Every crab makes a decision in that split second before it moves: fight, freeze, flee, or fade. They don’t choose wrong more than once. Here, hesitation means you get eaten. And if you’re lucky and quiet, you get to watch them make their choice. When they stop—when they finally wedge themselves beneath a rock or vanish into the reef’s contours—they don’t pant or pulse like a fish might. They just stop, as if nothing ever happened.

Down here, it’s not the fastest creature that survives. It’s the one that knows when to run, how to vanish, and what angle to take when it does. Crabs figured that out a long time ago.

The eyes are the first thing you notice, two dark marbles on stalks, swiveling like radar dishes in the murk. They move independently, scanning front and back at the same time, and it’s unsettling in a way I can’t quite shake. I’ve knelt in the silt, barely breathing, and watched a crab watch me, one eye fixed on my mask while the other seemed to scan the reef behind it, like it was calculating the best escape route. Or maybe waiting to see what I’d do next.

But crabs aren’t just watching. They’re communicating in ways most people never notice. They tap, drum, raise, and wave their claws in deliberate patterns, not just to warn or threaten but to talk. Males might flash their chelae, the front claws built like living pliers—part weapon, part tool—each ending in a sharp, hinged pincer. Look at me. I’m strong. I’m ready. Don’t come any closer. It’s a kind of semaphore, silent and specific, evolved not for show but for survival. Some species send messages through the seafloor by drumming with their legs.

The closer you look, the more the body itself becomes a language.

Beneath that armored face, their mouthparts are hidden in plain sight, tucked up under the shell like something secret. Most people never notice them. But divers have time. We wait. We watch. And if you’re patient, you’ll see those tiny, feathered appendages in constant motion, pulling in food, sorting it, filtering it, working like a factory line. It’s never still. Even when a crab looks motionless, it’s chewing through the world one particle at a time.

And they’re not picky. Crabs are opportunistic feeders—algae, plankton, fish scraps, rotting kelp, even other crabs if the tide turns cruel. I’ve seen it happen fast, almost clinical. No ceremony. No malice. Just need.

They speak through motion, posture, and action, enough where sound doesn’t carry and light doesn’t last.

Beneath the shell, hidden to most, lies one of the weirdest parts of crab biology: they breathe through gills, just like fish. The gills are tucked into chambers beneath the carapace, kept moist by leg movements and flaps called scaphognathites that pump water over them. I’ve seen crabs dug into damp sand during low tide, perfectly still but alive, waiting for the tide to return.

Here's something most folks don't realize: you can tell male and female crabs apart by flipping them over. Males have a narrow, pointed abdominal flap; females have a broad, rounded one shaped like a dome. That’s where they carry their eggs, thousands packed tight like orange caviar, gently fanned with back legs to keep oxygen flowing. It’s a strange kind of tenderness, watching it happen underwater. There’s something ancient about it. Something careful.

When you see a crab crawling across the bottom, it’s easy to think of it as just another bit of marine clutter, another scuttling shape in the gloom. But inside that shell is a creature perfectly engineered for survival, part armor, part instinct, part mystery. The more time I spend with them, the more I believe they’re not just part of the seafloor. They are the seafloor, living, crawling, biting proof that nature doesn’t waste time on beauty when function works better.

And still, somehow, they're beautiful.

Crabs aren’t just skittering distractions; they’re survivors in a complex life cycle that begins as floating larvae barely bigger than plankton. After hatching, young crabs go through multiple molts, shedding their exoskeletons to grow. These larval forms, called zoeae, drift with the currents—tiny, vulnerable—before settling to the bottom where the real battles begin.

Molting continues in adulthood. During these soft-shelled interludes, crabs are most vulnerable. Many hide in the sand or under rocks. For females, it’s the only time they can mate, making it a moment of both risk and opportunity.

Once fertilized, females carry eggs on their undersides like a clutch of orange grapes. Watching a crab fan her eggs with rhythmic leg flicks reminds you that even armored creatures tend their young with surprising delicacy.

Not all eggs survive, and not all crabs do either. For every empty shell tumbling in the current, another waits just out of view, ready to take its place.

As a diver, I’ve learned that the best moments often happen in the periphery. You come for the wolf eel or the octopus, but you stay because something small scuttles in and steals the show. Crabs are like that, endlessly watchable, hard-wired to move, eat, and thrive.

Next time you’re under the surface or in a tidepool, watch a crab at work. There’s a world in those legs, strange and alive as anything in the sea. A reminder, we’re only visitors in their kingdom.

Thom Robbins Bio

I am fascinated with the underwater world here in the Pacific Northwest. I have been a diver for over thirty years and have never been happier than underwater with a camera. I spend as much time underwater as possible, writing, shooting pictures, or teaching diving and photography. You can learn more about me at https://www.thomrobbins.com.

When not diving, I spend time with my wonderful, patient wife, Barb. We live in Shelton, Washington, where we relish a relaxed lifestyle close to world-class diving spots. Barb’s support has been instrumental in my passion for diving; she is my best and often harshest critic, constantly pushing me to capture better photos. Our 21-year-old son inspires me to be a better person every day. Completing our family are our two English Bulldogs, who bring us endless joy.

5 amazing hikes around Hood Canal

While there is plenty of news coverage following the devasting Bear Gulch fire near the Staircase Entrance to the Olympic National Park, don’t give up on your plans to visit the Hood Canal region to explore the many amazing hikes and trails in the area.

Update: July 29, 2025 – Until recently smoke conditions have remained “good.” As of 7/29/2025. fire activity has increased in three areas that have impacted Staircase Region and Olympic National Park as well as Upper Skokomish Valley and Hama Hama Recreation Areas. There is now increased smoke and conditions are unhealthy for some individuals in the immediate area.

Award winning local guidebook author, Craig Romano, shared 25 of his top area hikes with us in a handy “stuff-in-your-glovebox guide,” here are a few of the many hikes that are open and awaiting your adventure! Welcome to the #wildsideWA.

Tighten your laces!

1. Murhut Falls